You are here

Holdaway - The Pioneer of Ministry to Māori in New Zealand

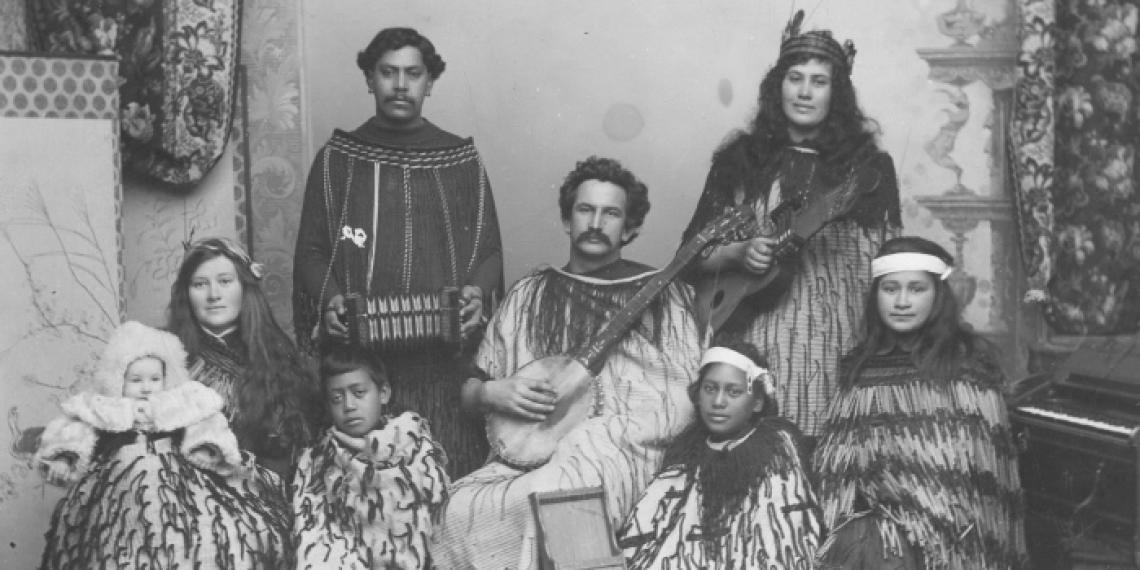

Holdaway (seated middle) and touring Māori Party, 1898

Māori knew him as Enata Horowe. His Pākehā name was Albert Arthur Ernest Holdaway and he was a formidable man. Ernest was born in Richmond (Nelson) in 1863 into a Christian (Methodist) home with strict temperance principals. When the Salvation Army came to town Ernest joined up and his mother Amelia encouraged him with an interesting reflection on what she might have done with the opportunity that lay before her son:

“Ah, Ernest my boy, if I had only had your chance, how much more I could have done for God! In England, we country children had to go and weed turnips for several hours in the early morning before going to the poor little school in the village, and return to the weeding after school was over. If could have had your opportunity and there had been a Salvation Army when I was a girl, what a worker for God I might have been.”

Indeed!

Ernest volunteered to become a Salvation Army Officer, leaving home on 24 February 1885 at the age of 21.

The Salvation Army formed a ‘Flying Brigade’ in 1885. It consisted of a covered horse drawn wagon fitted with four bunks. Under the command of Captain Dave Pattrick, it travelled the South Island, holding Salvation Army meetings wherever it stopped. Any method of catching people’s attention was employed, including humour. The four Salvationists on board were introduced this way:

“Captain Dave Pattrick – in command – 5ft 6 ½ins,

Lt. Ernest Holdaway – 6ft 2ins,

Lt. Woods – 5ft 10 1/2 ins,

Private A. H. Grinling – 5ft 11ins.

Total – 23 ½ feet fully saved.”

Holdaway and Pattrick - Flying Brigade

Ernest got to know ‘Maori Joe’ Solomon of the Kaiapoi Corps who both impressed Holdaway and established in him a great love for Māori. God was beginning to reveal the mission he had in mind for Ernest. In one of his letters he recounts this being made clear to him during a period of ill health:

“I have been ill with fever – unable to read, and brought down so weak as to be unable to walk. I could just lie there on my bed with the room darkened and think and pray. Whilst lying there, I thought a great deal about the Maoris, and I promised the Lord that if it was His will, I wold spend my whole life winning them to His Kingdom.”

Life in late nineteenth century New Zealand was not easy. Salvation Army officership was no exception. At Wanganui Ernest and his wife Elizabeth lived in a tent. As Ernest set about learning te reo Māori and looking for a place to start working with Māori he sent his pregnant wife to stay with her sister in Richmond. A daughter, Eva Aroha Holdaway was born and Elizabeth returned to Wanganui. Tragically Elizabeth contracted typhoid and was Promoted to Glory (died) on 2 March 1889. The Bakers, a household friendly to The Salvation Army, looked after Eva while Ernest pressed through his grief and pressed on with his mission. Brigadier Ivy Creswell writes “For nearly two years little Eva Aroha was cherished in the Baker household; but for her father, broken heartened on the river-bank, there was loneliness unspeakable. Yet his purpose remained unaltered and his faith unshaken.”

Elizabeth and Ernest

A widowed Ernest with Eva

There are many accounts of the results of Ernest’s unaltered purpose and unshaken faith. On one occasion a powerfully built and heavily intoxicated Māori man accosted Ernest wanting to address one of his Army meetings. Ernest told him he couldn’t, and that he had to be saved first. Indeed, Ernest did lead him to the Lord and Chief Tamatea Aranui of Ngatihau-Nue-A-Pararangi gave up alcohol and his pipe and became a stalwart friend of Holdaway’s. Tamatea gifted Ernest a 24ft canoe in which he and others set off up the Wanganui River stopping at Corinth, Athens, London and then Jerusalem.

Several dedicated young men were soon offering to help Holdaway with his work. Under his dynamic leadership, the influence of the Salvationists spread, and from Wanganui to Pipiriki and beyond, the Army cones become well-known in all the settlements, and the officers on every marae.

In December 1890 Ernest married Captain Agnes Alston. The Holdaways were promoted to the rank of Staff-Captain, and the work amongst Māori was given the status of a separate division. One of its greatest challenges was funding. Several Māori Party tours were led by Holdaway to raise funds for the work and Colony Commander Colonel Reuben Bailey instituted a ‘Māori tribute’ of not less than one penny per month on each soldier and recruit in the country as a further means of raising funds. He also approved of Holdaway’s suggestion that special language and practical training be given to the officers volunteering for this work, and to that end a 48 acre farm and a large house were leased at Aramoho.

Ernest, Agnes and Children, 1893.

Not all within The Salvation Army’s administration were as cooperative and encouraging. In January 1890, when the first edition of Te Pukapuka Waiata mo nga hoia o Te Ope Whakaora was in preparation, a whisper could be hard from the printing room: “Not very particular about another Māori job...Uses up too many K’s and g’s...” There was some consternation at plans in 1891 for an enlarged edition containing over one hundred songs and choruses, many of them newly translated or adapted. Ernest, who had spent more than a week in Christchurch “buried in translating, composing, and proofs” heard a compositor muttering, “Oh wretched man that I am! Who shall deliver me from this Holdaway?”

Perhaps because of the difficulty of financing the work amongst Māori, and that fact that many corps had not supported the Māori tribute, a complete change of policy was announced in April 1894. The Māori tribute was abolished and it was decided that a separate team of officers under the leadership of a staff officer could no longer be maintained. Evangelical work amongst Māori would have to be the responsibility of corps already established.

In districts with a mixed population it was planned to station one Māori-speaking officer and one English-speaking officer, with the aim of spreading Māori activity much farther afield than the Wanganui-Taranaki area, with less expense, but this plan was never effective put into operation.

The aim may have been laudable, and the financial problem was indeed acute, but much of the work accomplished in the previous four or five years was in remote areas where no other corps existed. The Māori Division was abolished, and Holdaway was placed in command of the Northern Division with headquarters in Auckland. It was no doubt a temptation for any colony commander to feel that a man of Ernest’s leadership and versatility should be used in a wider sphere than this work alone. However, the new arrangement heralded a sad decline in the Army’s work amongst the Māori of the Wanganui River.

Lack of continuity and long term planning undoubtedly affected the success of the Army’s work with Māori. With a new colony commander (Brigadier W.T. Hoskin) and a new Australasian commander (Herbert Booth), the beginning of 1896 heralded an unexpected reversal of policy. Holdaway was again “separated from the European work, and set apart as the apostle of the Māoris.” New corps, which included both Māori and European soldiers, had been established by the end of 1898 at Opotiki, Rotorua, Whakatane and Wairoa, and under the splendid leadership of the Holdaways things seemed set for further advances. But the New Year was to bring another drastic change.

The Holdaways were transferred to the staff of The Salvation Army Training College in Melbourne – never again were they to have the opportunity of carrying on the work for which they had a special calling. Ernest came back to New Zealand in 1908 but he was sent to Tasmania in 1910 to take command of the Army’s work there. Tragically he took ill with pernicious anaemia and was Promoted to Glory just four days short of his fiftieth birthday on 18 September 1913. Mrs Brigadier Agnes Holdaway was Promoted to Glory on 7 April 1952.

Sources:

Cyril R. Bradwell, Figh The Good Fight: The Story Of The Salvation Army In New Zealand 1883-1983, A.W. & A.H. Reed Ltd 1983.

Harold Hill (Ed), Te Ope Whakaora: The Army That Brings Life: A collection of documents on The Salvation Army & Maori 1884-2007, Flag Publications 2007.