You are here

The power of forgiveness

Forgiveness can be transformational, for individuals, families, communities and nations. What can we learn about the power of forgiveness through the people of Parihaka and Salvationist Maraea Morris?

Hunting for a bargain in a Family Store one day, I came across a t-shirt that I knew I had to buy right away. Across the front in big red lettering was the word ‘Arohamai’ and, underneath in smaller text, ‘remember Parihaka 5th November 1881’. Arohamai means ‘I’m sorry, forgive me’.

Just a few years earlier I’d never heard of Parihaka. I was never taught about it at school, despite it being an incredibly significant event in New Zealand’s history. I don’t remember how I first heard about Parihaka, but what I discovered changed my thinking about many things, including the importance of November 5.

I grew up always looking forward to November 5, it was the day we got to set things on fire, watch things blow up and marvel at the beauty of fireworks. While I enjoyed the sights and smells of fireworks—a weird tribute to a man who centuries earlier failed to blow up the British Parliament—Māori around the country grieved because of the horrendous acts of violence and injustice that occurred at Parihaka.

On the back of my new t-shirt it listed the reasons for the ‘arohamai’ on the front. ‘I’m sorry for the invasion of your village 5th Nov, illegal arrest and exiling of Te Whiti and Tohu, looting by the armed constabulary 18th Nov, destruction of your wharenui 20th Nov, forcible ejection of 1443 people from their homes 20th Nov, rape of your women, congenital syphilis in your children, and for the imprisonment without trial of 420 ploughmen and fencers for two years, lasting effect on their wives and children, the confiscation of your land, backdating of legislation to make legal the Govt’s illegal acts, and our failure as a nation to face these issues.’

The people of Parihaka have many reasons to feel grieved over what happened and the minimalising of events and intentional exclusion from the consciousness of all New Zealanders, through its absence in our teaching of history.

The peacemakers of Parihaka

Mahatma Gandhi is held up around the world as a shining example of non-violent resistance for the way he led the campaign for India’s independence from British rule. ‘I did once seriously think of embracing the Christian faith. The gentle figure of Christ, so full of forgiveness that he taught his followers not to retaliate when abused or struck, but to turn the other cheek—I thought it was a beautiful example of the perfect man,’ said Gandhi.

Yet a generation earlier, the prophets Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi of Parihaka had paved the way for ‘turning the other cheek’ through passive resistance, as a response to injustice and oppression.

Te Whiti combined Christianity with traditional Māori teachings and embodied the notion of rejecting violence even when resisting injustice. When the government tried to steal land in Taranaki, they took the words of Old Testament prophets literally and ‘beat their swords into plowshares’, and put fences across roads and ploughed disputed land. Many were arrested and sent to forced labour in the South Island.

Maraea’s miracle

Maraea Moana Mahaki, also known as Maraea Morris’ life has been beautifully captured in Liam Barr’s artwork entitled ‘Salvation’. Hers is a story of devastating loss, all-consuming grief and freedom through forgiveness. Three years after marrying Pera Taihuka, a young chief, he was executed in front of her eyes after they were both caught up in the Matawhero massacre, a short distance from Gisborne.

‘Wiping her hands in her husband’s blood, Maraea vowed that she would not rest until she had taken the life of Te Kooti Arikirangi, the Māori dissident,’ wrote Joan Hutson. Vengeance consumed her for over 17 years, as she searched everywhere for Te Kooti. She eventually returned to Gisborne and found herself on the outskirts of the crowd that had gathered when The Salvation Army ‘opened fire’ and marched up one of the main streets.

As a child, she’d grown to love the Bible and prayer after attending a school run by the Wesleyan Mission, and later attended the Māori Church of England, but that had all but disappeared, as her quest for revenge consumed her life. She still read the Bible but it provided no light to her life—until she heard Captain Ernest Holdaway read from the final chapter of Revelation, ‘familiar words that riveted Maraea’s attention ... let in the first glimmer of light,’ wrote Brigadier Ivy Cresswell in her book Canoe on the River.

A few days later Maraea met Cadet Grinling in the street selling the War Cry. She asked him for a copy for free and as he gave her one he smiled and said, ‘God bless you’. She then saw the Captain going to her neighbour’s house. He asked Maraea if she was a Christian and did she love God. At first she replied only in Māori, before eventually declaring in English, ‘I am a heathen’. Earnest took that as an invitation to tell her all about salvation.

Maraea described her conversion experience: ‘One Friday night, 26 days after the Army began in Gisborne, I came forward and knelt at the front. They all prayed for me, but it was no good; my heart was stubborn.

‘I went home and prayed. Oh, what a miserable week I had! I couldn’t get rid of the Devil, and God wouldn’t have anything to do with me. Then the captain came and talked with me, and I told him some of my story. When I told him about my husband’s death, he saw that I was angry. He asked me could I forgive Te Kooti for Jesus’ sake? I said, “No!” Then he prayed for me to have the power to forgive my enemies, and all at once a light broke in upon me, and I cried for forgiveness.

‘I pardoned Te Kooti, and I felt my own sins were forgiven from that moment and I knew I was saved. After this I was so happy; I began to understand my Bible. I used to read the hymns and I prayed constantly.’

The transformation in Maraea was a miracle. She became highly respected and radiated light, described by some as a ‘veritable terror to evil-doers’. With her distinctive moko on her chin and Bible in hand, she told her story over and over again, even touring throughout New Zealand with Ernest Holdaway. She felt particularly called to urge Māori to come to Jesus.

In September 1890, Maraea went to the Congress in Melbourne and shared her story. Her final words to those present were, ‘The God who saved me yonder in New Zealand is able to save you’.

Owning our actions

The Crown officially apologised to the people of Parihaka in June 2017, and as the then Treaty Negotiations Minister Chris Finlayson read out the apology, people openly wept. Ancestors from both sides of the events were present at the apology, and Warren Sisarich, whose great-great-grandfather was part of the constabulary who took part in the ransacking of the settlement said, ‘Maybe it’s time we started admitting our faults and seeking forgiveness and saying sorry.’

Chris Finlayson said, ‘Ultimately there can be no reconciliation where one party remembers while the other forgets.’ That has been one of the difficulties of Parihaka—for so long, the only ones remembering the actions that devastated an entire community of people, were the victims and their whānau.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, set up to investigate allegations of human rights abuses during the apartheid era in South Africa. He said, ‘Without forgiveness, there is no future’. The process could not erase the actions of the past. It could not bring back those who had been killed. But what it could do is give a platform for those who were victims of the atrocities to be heard, to have their grief acknowledged and begin the process of reconciliation.

The courage to forgive

There is no magic trick to forgiveness. For Maraea, she never heard Te Kooti acknowledge the pain and trauma his actions caused. She never received an apology from him. But, she still forgave him. She made a choice to forgive him for what he did. And that choice broke the chains of darkness over her life and let in the light. She had been a prisoner, bound by her anger, desire for revenge and grief, all the while, Te Kooti probably never gave her a second thought.

What Maraea’s life demonstrates is that God is able to make a way, when it appears that there is no way. The Holy Spirit was able to help her ‘let go’ and experience real freedom. God’s love for Maraea was more powerful than her hatred for Te Kooti.

Did she forget what happened? I don’t think anyone could ever forget something like that, but she was able to move on from the toxic emotions that unforgiveness breeds. If you’ve ever watched—and been terrified by—the movie Jaws, you know that it’s the soundtrack that causes all the emotional turmoil. Mute that and you have this weird, sometimes soothing and definitely unrealistic mechanical shark.

It is as if the Holy Spirit pushed the mute button on the ‘soundtrack’ of her tragedy, allowing her to not be held hostage to the emotions of the events.

Maya Angelou said: ‘You can’t forgive without loving. And I don’t mean sentimentality. I don’t mean mush. I mean having enough courage to stand up and say, “I forgive. I’m finished with it”.’

It was God’s love for, and forgiveness of, Maraea that changed her life. Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:44, ‘But I say, love your enemies! Pray for those who persecute you!’ would have once felt impossible to Maraea. But as she grew in her faith and experienced transformation in her own life because of God’s love, what was once impossible, would have become part of her testimony to the power of forgiveness.

Our future depends on it

Richard Rohr said, ‘God created us for love, for union, for forgiveness and compassion, and, yet, that has not been our storyline. That has not been our history.’ Around the world, indigenous cultures have been on the receiving end of some dubious decisions by missionaries—representing the love of God and the person of Jesus. The Church partnered with the Crown and lost sight of the imago dei in the people they were engaging with.

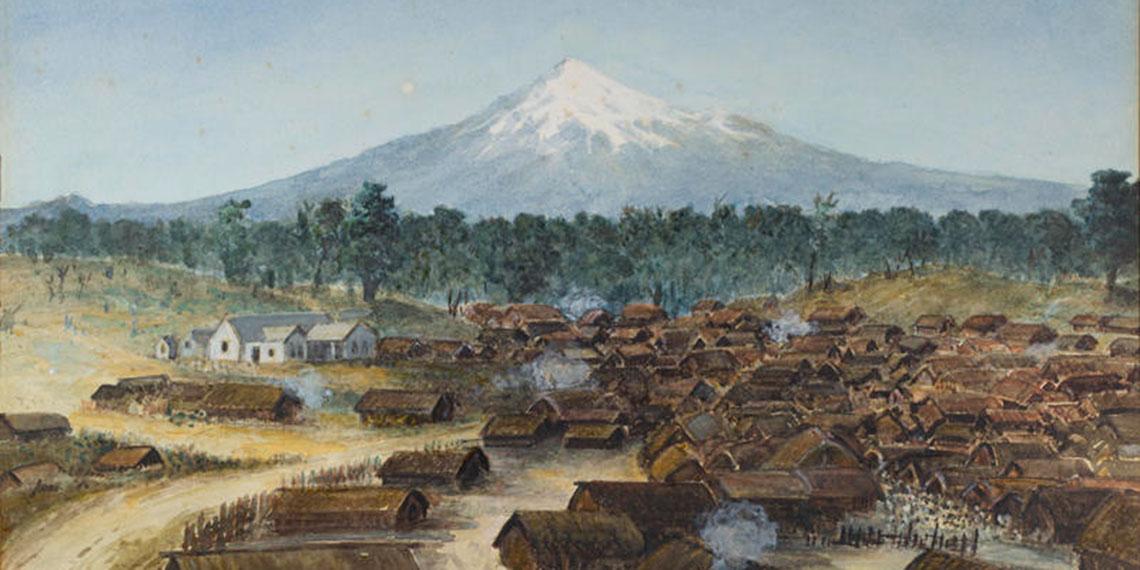

Parihaka stands as a reminder to all New Zealanders that injustice is real—it scarred the land and the people of Taranaki for generations. It also reminds us of the power of the Gospel, of non-violent resistance in the face of brutality, and more importantly of the power of forgiveness as the pathway to healing and restoration.

Maraea Morris’ life is a beautiful picture of what happens when we forgive our tresspasses, and accept the forgiveness of God for ourselves.

Peter asked Jesus how many times he should forgive someone who sinned against him. He offered seven as a possible number. But Jesus said, seventy times seven. Jesus wasn’t suggesting that Peter keep a tally until he reached 490. Rather, that Peter needed to expand his heart and make room for grace and forgiveness the way God does with us.

Forgiveness—it’s simple but not easy. Just ask the people of Parihaka and Maraea Morris.