You are here

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Rangitiratanga and Democracy

In Aotearoa we are proud of our democracy—the idea of ‘one person one vote’. It is the very essence of an equal and fair society. For the most part it is good but, as Winston Churchill once said, ‘democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried’. Democracy has its flaws, and one area of deficiency is in regard to minorities. If a particular ethnic group is in the majority, then the ideas, wants and needs of that group will often be prioritised—unless checks and balances account for this.

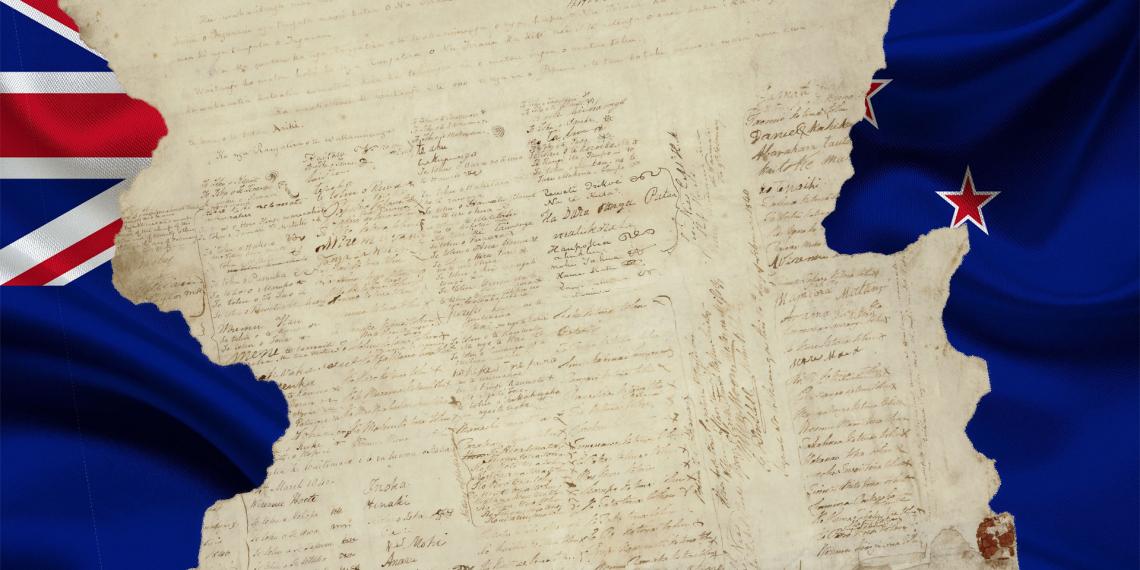

In New Zealand we have Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a document that sought to ensure that rangatiratanga (self-determination) for Māori, as the indigenous people, was maintained. However, New Zealand’s democratic system has continued to override any right Te Tiriti sought to uphold. After all, it was within the New Zealand democratic system that, over time, Māori experienced the loss of their land, culture, language and the possibility to flourish under their own steam. Sadly, when Māori encounter the various institutions of the state today, their experience is often negative and even traumatising—think imprisonment, unconscious bias within the police force, uplifting of tamariki from their whānau by Oranga Tamariki, and other forms of at times culturally unsafe or even racist environments in many other NGOs.

It is hardly surprising that in this context Māori find themselves represented in all the worst indicators of marginalisation—including crime, poverty, educational underachievement and homelessness.

Much has been done to ensure that Māori are involved in matters that affect them. Public institutions are striving to be more culturally responsive and inclusive, and to ensure that kaupapa Māori services are run for Māori whānau. Examples of this included the establishment of Māori wards in local councils and Te Aka Whai Ora (the Māori Health Board) which enabled partnership at a governance level. The increasing investment in and teaching of te reo Māori saw the rise of te reo Māori use which aided the strengthening of Māori—a culture and identity that is unique to New Zealand. There has also been an increasing number of kaupapa Māori programmes and initiatives developed.

It is therefore disappointing for New Zealanders to see a new political environment where many of these hard-won advances in social policy are being reconsidered and even undone; winding back support for te reo Māori use and education, inferring that any initiative designed to specifically address Māori disadvantage is ‘race based’ and should be re-evaluated, and disestablishing Te Aka Whai Ora (the Māori Health Authority). More recently we have seen the idea raised that Te Tiriti principles need to be redefined—presumably to further neuter any of the more problematic articles in Te Tiriti that promise Māori more involvement in and say over their own destiny.

Māori have been on a long journey trying to regain the rangatiratanga that was promised to them within Te Tiriti, and it had seemed that some progress was being made. Māori are therefore understandably extremely upset by these developments, and many Māori and Pakeha are expressing their anger and seeking to hold the government to account and to turn these manifestly unjust and backward steps around.

The government is instituting these changes with support from an electorate which constitutes a largely non-Maori majority. To honour Te Tiriti, what is needed is for the non-Māori majority to understand our history, to honour the covenantal commitments made to Māori and to support developments like many of those now being unwound.

All of this in the hope that the original people of this land can flourish, in contrast to much of the current pain and dislocation that colonisation has wrought across Aotearoa New Zealand.

By Lt. Colonel Ian Hutson, Director - Social Policy and Parliamentary Unit