You are here

From there to here

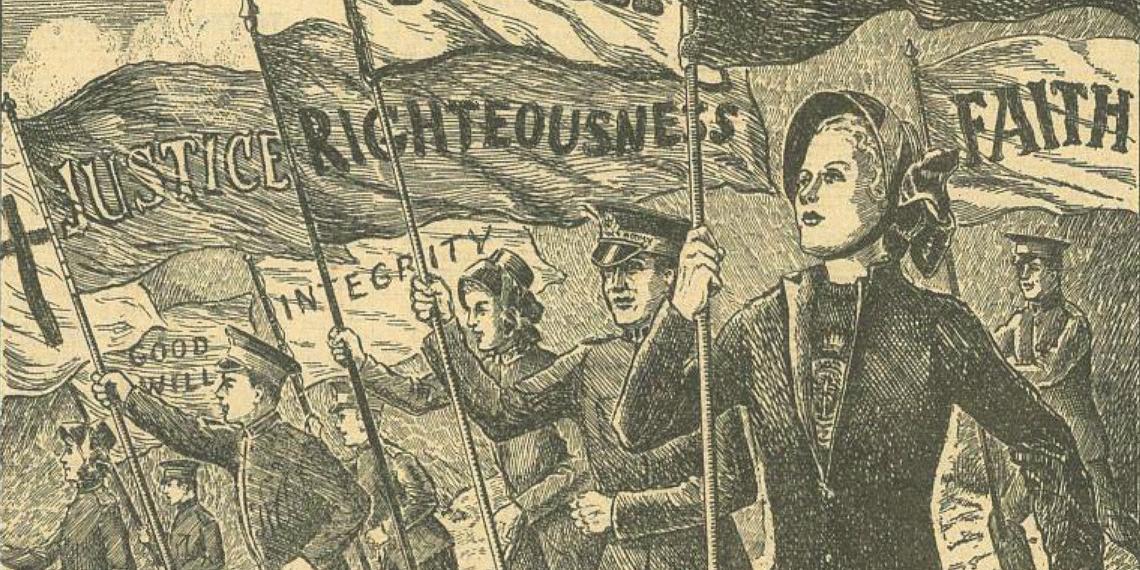

For the first time in our territory’s history, women outnumber men on executive leadership. The Salvation Army works against the discrimination of women in the public sphere, but it has taken a long time to gain equality in our own ranks. In celebration of the anniversary of our nation’s suffrage, War Cry takes a snapshot of the journey from ‘there to here’.

On 19 September 126 years ago, New Zealand women were the first in the world to win the right to vote. Kate Sheppard was without doubt our most famous suffragist—her face now appropriately gracing our $10 note. What is less commonly known is that Kate was also a member of the Christian Women’s Temperance Union, and the first president of the National Council of Women—exemplifying the influence of Christianity on first-wave feminism.

Many of Kate’s views, therefore, reflected that of Salvation Army co-founder Catherine Booth, who—half a world away in the East End of London—was also fighting for women’s rights. Both women were gifted and influential leaders who achieved marked success in the fight for equality during their lifetimes.

A radical vision

Catherine was particularly radical for her time, and as early as 1878, she had thoroughly convinced her husband William of the right of women to preach, lead and undertake any ministry task for which they were gifted.

While other denominations emphasised biblical passages that appeared to prevent women from full participation, Booth ably reinterpreted them within their biblical historical context, and highlighted the many other passages to the contrary. She believed that ‘the word and the Spirit cannot contradict each other’, and silenced her opponents by asking why God would prevent half the Body of Christ from attending to the urgent work of the Great Commission. After all, she affirmed, the Scriptures declared that the Spirit would be poured on both sons and daughters.

Catherine was a trail blazer for a woman’s right to lead and minister alongside men in the church. She also called for fulfilment in Christ, where all sense of women’s subordination to men be redeemed. This is the ethos upon which The Salvation Army in New Zealand was founded in 1883.

Leadership based on merit not gender

Indeed, women in the early Army were fully involved in the mission. In her thesis, Gender Equality in The Salvation Army in NZ, 1883–1960, New Zealand historian Raewyn Hendy writes:

‘Prior to World War I, particularly in the period from 1883–1900, women officers were able to participate in most aspects of the work … with positions appearing to be allocated on merit and availability rather than on gender.’

Written in 1895, the International Orders and Regulations for staff and officers of The Salvation Army were remarkable, stating: ‘No woman is to be kept back from any position of power or influence merely on account of her sex’.

Raewyn uncovers some fascinating traces of the voices and stories of women serving in New Zealand at its inception, such as Lieutenant Annie Barriball and Captain Emily Andrew, who began the work in Norsewood—a small settlement in Hawke’s Bay—in 1891.

An article written in the local paper by the Lieutenant gives no indication of the officers’ gender, but simply depicts Annie and Emily as, ‘trained ministers establishing a church community, preaching and leading worship, and ministering to the needs of their congregation … and undertaking identical tasks and responsibilities to that of a male officer’.

Raewyn affirms that ‘this article gives the impression that gender inequality was not an issue in The Salvation Army in New Zealand at this time.

‘The decade of the 1890s represents a highpoint for women in The Salvation Army in New Zealand. This coincided with increasing activism by many New Zealand women around issues of suffrage and moral and social welfare. The Salvation Army in New Zealand saw that women’s rights were an important issue at this time and chose to emphasise the organisation’s position on equal opportunities for women as a way to draw attention to its evangelistic message and to engage with the wider community.’

The era of conformity

But Raewyn’s research concludes that, ‘In the years from 1920 onwards, The Salvation Army increasingly conformed to the gender roles of the wider New Zealand community and full equality of roles and opportunities for women was not fully implemented by the organisation.’

By this time, The Disposition of Forces—a telling document of how The Salvation Army viewed gender roles—changed from the gender-neutral listing of all officers by surname and rank, to female officers’ names being italicised. Married women officers weren’t even named but denoted only by a (+) after the husband’s name.

Orders and Regulations for Field Officers in 1960 includes a very revealing section entitled ‘an officer wife’:

‘Upon her depends her husband’s wellbeing and success … [she should] stimulate him to rise to the highest standard of which he is capable … guarding, supporting, assisting … [with] carefully prepared meals, economy in outlay of income, agreeing to his absence, sparing him anxiety over home and children.’

The extent of the modern Army’s failure to fulfil the Booths’ vision is clear in instructions to the officer wife such as: ‘Her service will depend largely on her husband’s appointment,’ and, ‘an officer wife should assist her husband’. Perhaps most telling is the injunction that if he has a headquarters appointment, she is no longer his second in command, but ‘should serve to the best of her ability as a soldier, and if desired a local officer of the corps to which she belongs’.

The Army subtly shifted from a strongly egalitarian position to a complementarian one.

Conclusions that speak for themselves

War Cry asked Raewyn to comment on how she felt about her conclusion that the Army largely failed to practice its position before 1960. But as a disciplined historian she replied, ‘It’s not for me to have feelings about the research—the conclusions speak for themselves. It’s up to The Salvation Army to interpret the findings for its context.’

But Raewyn did make several observations:

‘I certainly noted the under-utilisation of women married to men with headquarters appointments. In the 1950s, in particular, married women officers never gained the experience to hold an appointment in their own right because they were largely kept in the home sphere. And while single women seemed to have more opportunities to lead at this time, they were blatantly kept from extending their capacity because larger corps appointments were reserved for married couples.’

Raewyn observes the notable shift from an Army that began as a ‘radical and unconventional denomination with women highly visible’, to one that reflected traditional gender roles.

‘From the 1920s to the 1960s the idea of equal roles and opportunities was definitely out of step with the prevailing culture—both secular, and the wider religious world in New Zealand. She would have been a very brave woman who chose to step out of the prevailing culture’s homemaker role!’

Returning to the vision

What happened to William and Catherine Booth’s radical vision for the equality of men and women?

Gender equality continues to be a complex issue in The Salvation Army. While the turn of the 21st Century has seen good forward movement, many women officers serving today—both single and married—still describe subtle hints of discrimination that hinder the realisation of the Booths’ vision.

This was confirmed by the 1994 International Commission on the Ministry of Women Officers, which reported, ‘It is recognised that considerable changes in thought patterns and administrative practice would be needed to achieve full equality for women officers’.

In his 2012 research paper Women at War: A Contrast between the Theology and Practice of Women’s Officership in the Contemporary Salvation Army,’ Major Ian Gainsford concludes that ‘essentially it is clear that the Army’s [theological] position is not in question—it’s practice, however, is.

‘To align the Army’s belief and practice is not hopeless, but it will be hard,’ Ian says. ‘Such reform may be difficult and at times painful, but by the grace of God it is well within the Army’s reach.’

Today’s women speak

War Cry asked a cross-section of generations of women serving in The Salvation Army—officers, soldiers and employees—what has changed for women in their lifetime, and what the Army could be doing to realise equality.

One of those respondents was Northern Divisional Community Ministries Director Rhondda Middleton, who believes she has had greater freedom to lead as a non-officer woman, saying that it’s her experience that qualifies her for her current role. ‘My gender has been irrelevant during the past 18 years of employment with The Salvation Army,’ she says.

Married female headquarters officers often did not get independent appointments until 1997, when Commissioner June Kendrew (now retired) was appointed as Territorial Women’s Ministry Secretary—an international first. Advocating strongly for the development of women during her senior leadership tenure, June observes that much of the discrimination she faced following her training in 1960 is now being addressed by leadership.

Like Rhondda, Northland Bridge Director Major Sue Hay affirms that as a woman working in the social sphere, she’s been ‘accepted as a leader based on my skills and clinical qualifications. In New Zealand’s current cultural context, I do not experience barriers based on gender’.

However, Sue believes there’s still much work for The Salvation Army to do. ‘We need to explore how to appoint people into very senior roles which match their gifting rather than our current gender-based roles and responsibilities.’

Central Division Secretary for Programme, Major Christina Tyson, agrees. ‘There’s still a need to challenge the culture that says if women lead, they are best to do so in a particular way. A lot of women have great ideas but continually need to lobby and persuade (which takes time), rather than simply set a course.

‘Males seem able to make decisions and take the lead, while women must tread cautiously—when we don’t, we can be labelled “bossy” or “demanding”. Strong leadership in males is viewed as a character strength, while in females this can be seen as emasculating of males.’

Echoing Christina, Sue raises an important point: ‘I don’t think we teach enough on how to live as equally-valued in our relationships when our roles hold different levels of organisational power.’

Northern Divisional Director of Women’s Ministries and Divisional Secretary for Personnel, Major Liz Gainsford, states that, ‘I’m determined to play a part in changing the culture of the Army for women—but this starts with me. If I’m not prepared to be intentional in my own development, to speak out, and to be in the room when important discussions are happening, then things will never change.’

A voice from the past with a message for today

An 1891 issue of War Cry records the words of Staff-Captain Emily Grinling, and they are as true today as ever they were: ‘Salvationist women of New Zealand rise up … go forth to fight bravely … and do your part in the great salvation war. Lasses, live up to your privileges and stand up for your rights!’

by Jules Badger c) 'War Cry' magazine, 21 September 2019 p6-9 You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.