You are here

Welcoming Refugees

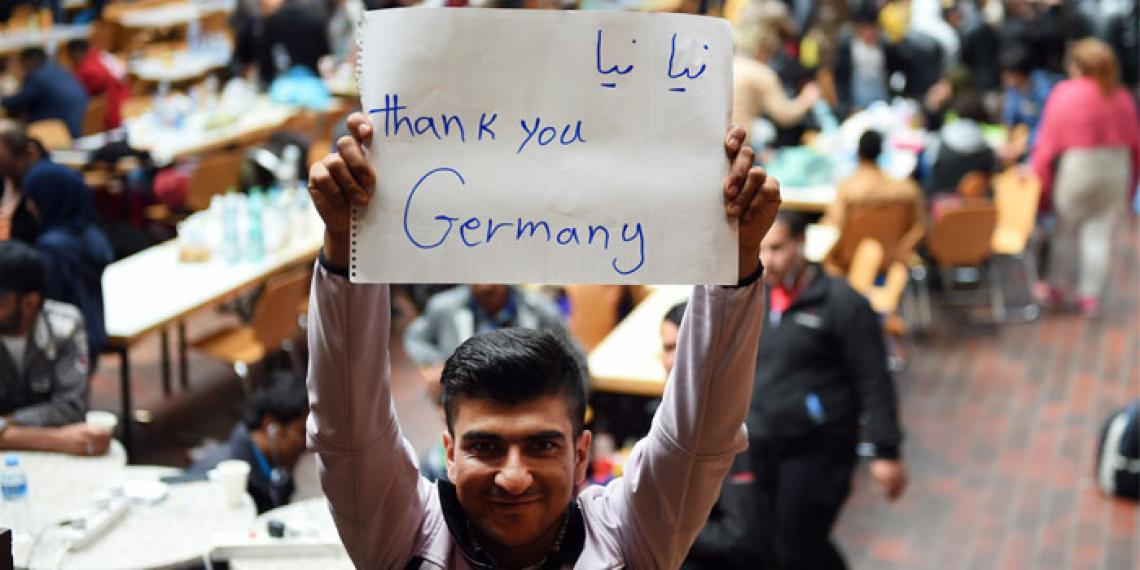

Germany has made space for more refugees than any other European country. Salvation Army officer Captain Ollie Walz and his wife Christiane have been leading The Salvation Army’s response in Solingen, a city of 155,000 people between Düsseldorf and Cologne.

By August 2014, the United Nations’ refugee agency, UNHCR, reported that the number of people forced to flee their homes across the world had exceeded 50 million for the first time since the Second World War—an

increase of six million from 2012. Aid agencies were struggling to cope with the emerging humanitarian crisis.

More and more people were making dangerous journeys across borders by boat and then on foot to flee violence and war. Many were from Syria, which had already suffered an influx of refugees from Iraq and was in the grip of civil war.

Toward the end of 2014, Ollie and his wife were in their car coming home from a Salvation Army territorial leadership conference, listening to a news report about refugees on the radio. ‘We said to each other that it was clear this would be a big thing in Germany,’ Ollie recalls. ‘We weren’t sure at all of what we could do, but already we could see that the refugees would come with so many needs.’

On the Monday after, the local newspaper ran a story saying The Salvation Army was receiving donations of clothes for refugees—even though Christiane had not been asked about this. She and Ollie only found out when a TV station phoned to ask how the clothing appeal was going. ‘That was the first we heard,’ says Ollie, ‘but we felt this was God’s way of saying to us that we must care about the refugees.’

Germany is an attractive destination for refugees because it has a good government and a strong economy. ‘A lot of countries were saying, “We don’t want refugees—we don’t like you and you’re not welcome.” And so they offered no food or support. And, of course, some countries are very poor and did not have the resources to help. Austria was welcoming, for example, but is a small country.

‘But then our German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, said, “We will welcome all refugees.” I was so proud of the German people! To see in Munich hundreds of people come to the train station with food and clothes, and nappies and toys for the kids. I was proud of our very strong welcome. The Germans saw how bad the situation was for the refugees and it touched their hearts.’

Rallying the troops

Ollie and Christiane are corps officers (pastors) of a Salvation Army church congregation—or ‘corps’—of around 30 people. Ollie says while that sounds small, in Germany, it is a fairly typical size for The Salvation Army.

The couple, who are in their mid-30s and have four children aged from four to 13, also oversee the Army’s youth work in Germany, Poland and Lithuania. But life was about to get busier.

‘Our first problem was what to do about receiving the donated clothes,’ Ollie says. ‘We started by putting out a basket in our second-hand shop with a sign that said, “For refugees”. But in just over one week, we received two tonnes of clothes—too much for our small shop to handle. So we moved our Volkswagen out of the garage and stored the clothes in there. Within a week our garage was full. The German people were so generous. They gave us good, new stuff for the refugees. Not rubbish. It was amazing!’

As the refugees poured across the German border from Salzburg in Austria, they were taken to a large refugee centre in Rosenheim for processing. When refugees arrive in Germany, they are allocated to refugee camps in various cities, staying for two to three weeks at most. From there, they are helped into accommodation in flats—often in a third location, but with some staying in the same city.

‘Our cities didn’t really know how many refugees were coming, so at the beginning it was a real learning process for all of us to find out the good way to help,’ remembers Ollie. ‘Everyone in Solingen was really struggling at first. We were learning all the time about the best systems to help people.’

Initially, Solingen turned its school gym halls into refugee camps. ‘The men were on the right-hand-side, the women on the left. It was just bed, bed, bed—no privacy. And kids were running everywhere. It was a very strange atmosphere.’

Last August, with the gym halls full, Christiane and Ollie went to a new refugee centre set up in an old government building just 200 metres from their house. ‘We simply asked, “What can we do to help you?”

‘The man we talked to did not know The Salvation Army, but he was happy we came. I told him that we could not help with personnel because we were only small and all our people work, but we could help with clothes and toys for the children. We also offered to create a children’s room at the centre—to paint and fit it out for the kids.’

Those from the Salvation Army corps were eager to show their support. One of them suggested their brass band could play for the refugees, and the refugee centre said yes. ‘So we went, taking helium balloons for the kids, and our band played. We decided not to wear Salvation Army uniform, because the refugees don’t understand it and some come from countries where the military is not friendly—many have left their countries because of war. So only a few of us wore clothing with Salvation Army branding.’

Almost 200 people came to the outdoor concert. ‘They were dancing, clapping and laughing—they had a great time! And our Salvation Army people were really touched by the refugees as well.’

The blessing of helping others

They went ahead with transforming a room at the centre for children, and now run a children’s programme that includes making balloon animals, craft, singing and food. The aim is to give the children a good time, a touch of normality.

Ollie says you don’t have to scratch below the surface very far to see the effects of trauma on these young lives. ‘When a balloon pops and children huddle together in fear, you have to think about what they have experienced.’

The Salvation Army doesn’t want to inflame religious tensions, and for that reason does not include any Christian component in its children’s programme, Ollie explains. ‘One day, a child whispered to our assistant, “Are you Christian? I am also a Christian.” For some who come from Muslim countries, this is a secret—their Christian faith is not something they can speak about—so I don’t want to pressure them about Jesus. We’re not doing this to make Christians, but to help people in their need.’

He says the children have now become so familiar with The Salvation Army, they will often simply walk through the door to the Army hall whenever it’s open.

The corps’ initial support for the refugee centre in their neighbourhood was extended to providing clothes and toys to five centres. During the busiest part of the refugee influx, these items were usually distributed on a Friday.

The hall where Sunday church services are held was emptied and clothing moved in. A table with coffee and cake was laid out to help people feel welcome, with a separate area for children to play.

Those distributing clothing soon learnt that different cultures had different ways of choosing their clothes. ‘People from Africa would stay four hours and look over and over the clothing, with the whole family and children chatting and being together, but those from Arabic countries of Syria, Iraq and Egypt were very quick—just a few minutes,’ Ollie says.

They also learnt the blessing that comes from helping others. ‘To give a man a pair of trousers, or a child an old teddy bear—they’re so happy! It’s really amazing how grateful people are.’

With more distant borders closing, meaning less opportunity for refugees to make it to Germany, the need for clothing has decreased, so people now go direct to The Salvation Army’s second-hand store, rather than its hall.

However, a more recent development has been opening the corps’ kitchen to refugee women. When Ollie and Christiane were first appointed to Solingen, the kitchen was in a very bad way. The Salvation Army had put on a Saturday meal for the homeless and the elderly for 20 years, but the kitchen was long overdue a costly makeover. With funding support from Norway and Canada along with other sources, a cramped and ill-equipped kitchen became a great space that offers another precious touch of normality.

On Fridays, women from the refugee centre have an open invitation to bring their food (purchased from a small allowance they receive) and cook a meal at the Army hall. ‘We look after the kids, while the women cook together,’ Ollie explains.

‘It’s not just about food and cooking; it’s about fellowship. They have great fun, chatting and laughing. It’s like being a “normal” person again, enjoying something that they would have been able to do in a more peaceful past. They can also enjoy food that has the taste and smell of home—Arabian food, not European food.’

Compassion in action

The Salvation Army’s profile in Solingen has lifted because of its refugee work, but Ollie is more excited that, as the refugees have come to know The Salvation Army, the first step in a relationship has been formed. ‘They will look for us again,’ he says, with certainty. ‘Besides, this is really the work The Salvation Army hasto do: to see the need of people and be there to respond.’

Unsurprisingly, Ollie now has a far greater empathy and compassion for the plight of refugees. ‘Their lives were in danger,’ he says, struggling to find the right English words to explain what is in his heart. ‘When I think about what they’ve done to reach Germany … you talk to people and they are crying as they share their hard stories. Some have children just one or two years old, and they’ve put them in small boats and then carried them hundreds of miles.

‘As a parent, I can’t even imagine what it is like to be so afraid for your children, so desperately in need of hope and security.’

As well as developing empathy for refugees, Ollie says he has gained a deeper understanding of the Bible. ‘I now better understand what it meant for Jesus to be a refugee child. I read the Old Testament and understand what it is like to go out from your country to be a refugee.’

Those who attend the corps have also benefited from serving.

‘A member of our music team had a child come and give her a big hug to say thank you—this was for her a special moment. ‘So we have given, but we have received back love. You can see the heart of our people, some of whom had to leave their own homes after the Second World War and were helped by The Salvation Army. Now they are supporting and praying for the refugees—they are giving back. Of course, we will stop when we are not needed. We have learnt to be flexible, to look for the next thing to help people.’

Ollie understands why some people are not happy to see an influx of refugees to their country, but he says selflessness is a sounder path than fear and hatred. ‘Many people are afraid of what welcoming refugees will mean for their own income, for instance. For Germans, to get housing can be hard, yet we are finding flats for refugees. So it is a challenge to support refugees, even for a well-organised country like Germany.

‘But we have welcomed them anyway, because it is the right thing to do. Now, we will support them to integrate, helping them learn the language and culture and get work, so they become part of Germany.’

Support the #WithRefugees petition

by Christina Tyson(c) 'War Cry' magazine, 23 July 2016, pp 5-7

You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.