You are here

A glorious ruin

As we prepare to celebrate the great moment in history when God came to the rescue of our ‘glorious ruin’, we ask: What do we really mean by this mysterious salvation?

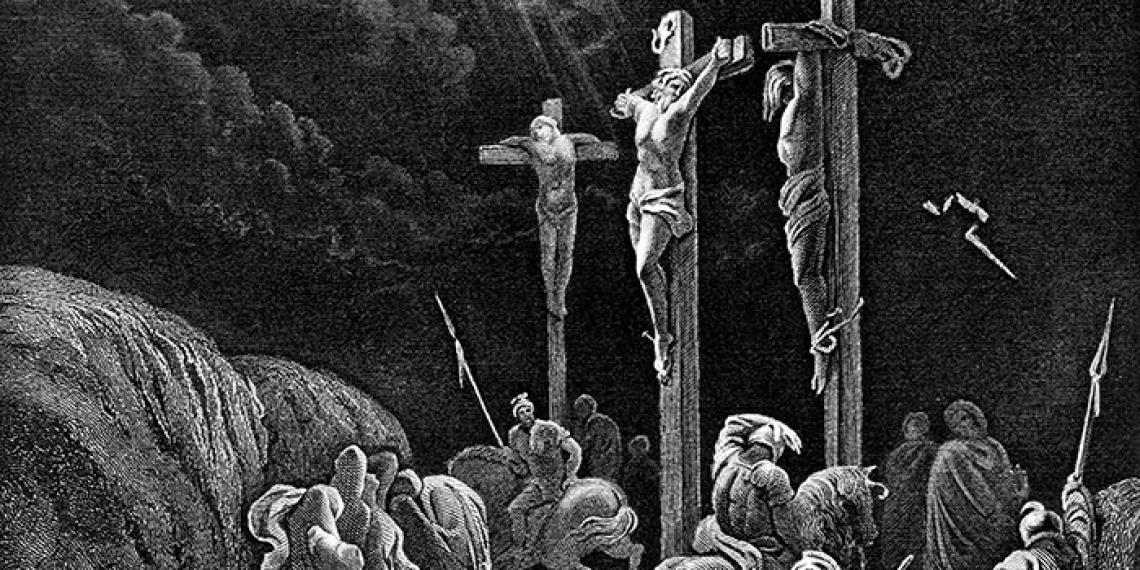

Christian communities across the globe are once again marking a very significant festival in the Christian calendar—the season of Easter. Millions of believers of all faith traditions meet as the body of Christ during Lent, to remember and mourn the difficult steps Jesus took to his crucifixion, and to celebrate his resurrection from death on Easter Sunday.

The Resurrection is the climax in the story of God’s redemption of the world. Indeed, it provides the foundation of Christianity, and establishes Jesus as the second person of the Trinity. He is God incarnate, both altogether God and altogether human. He is our Lord and Saviour.

A living hope

Christians have always believed that Jesus Christ is both Lord and Saviour, and they have sought to keep the two titles inextricably tied together. Any formulation that undermined ‘salvation through Christ’ was rejected—as was any view of salvation that left room for other lords and saviours or for salvation by other means.

In light of this, Christians have also always believed that anyone who chooses to follow Jesus receives ‘…a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead…’ (1 Peter 1:2). Through faith in God, those who follow Jesus receive salvation and may walk in a new way of life (Romans 6:1–9).

At the heart of the ‘work of Christ’, is the Christian belief in Christ’s atonement. Atonement is an English word that means reconciliation, and refers to the work of Christ by which he brought humanity and God together in spite of humanity’s sinfulness and God’s holiness.

This is echoed in our Salvation Army doctrines which state that ‘the Lord Jesus Christ has, by his suffering and death, made an atonement for the whole world, so that whosoever will may be saved’ (Article of Faith 6).

Our statement of faith is in no way unique. All the major Christological creeds say that Jesus Christ is Lord and Saviour, but none sets forth what Christians must believe about how he saves. In other words, there is no uniform Christian doctrine of salvation.

Beyond words

The early church believed that ‘God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ … ’ (2 Cor 5:19). In some mysterious way, beyond full human comprehension, Christ’s death on the cross was a sacrifice for sin, a conquest of evil powers that enslave, and an example of perfect love for disciples of Jesus Christ to follow. We still hold to this!

Wonderfully, there is a tremendous diversity of language and a kaleidoscope of imagery both in the biblical story and church tradition that attempt to explain what Christ has done. They all add to the picture—but no one explanation does justice to all that happened on the cross. The Arminian Baptist theologian Roger Olson describes it as both ‘objective’— in which something happened in the cosmic, divine order of universal history; and, ‘subjective’—in which each of us is drawn to God in repentance and faith. In other words, Christ’s death and resurrection changed the world, apart from anyone’s response to them. Nothing is, nor can be, the same again.

But the change wrought by Christ happens in the life of an individual when that person responds to the life and teachings of Jesus. Olson summaries all this by stating that ‘Jesus Christ’s incarnation, life, death, and resurrection [I would add ‘and ascension’] objectively provide for reconciliation between God and humanity and make possible forgiveness and transformation of those who believe and trust in him’.

A glorious ruin

In thinking about this, I have found the writings of CS Lewis and the protestant theologian Paul Tillich, insightful. They both speak of what it means to be human now. Lewis describes humanity as a ‘glorious ruin’—‘glorious’ because God created us ‘…a little lower than the angels…’ (Psalm 8:5–6), and honoured us with the role as his vice-regents on earth; ‘ruin’ because we have made such a mess of what God intended for us.

Similarly, Tillich says we are both ‘essentially good and existentially estranged’. We are wonderfully knitted together in the image and likeness of God, but in the reality of our current existence we are estranged from the ultimate source of being and meaning.

This paradox of human existence also manifests itself in estrangement from our own true selves, in estrangement from others, in estrangement from the rest of creation and in estrangement from life as God intended it to be. But it does not have to be this way. Tillich goes on to explain that only reunion with God, initiated by his grace, has the power to overcome our estrangement.

Creation healed

One biblical portrayal of salvation is ‘as being healed’; and, according to Wesleyan theologian Howard A. Snyder in Salvation Means Creation Healed, ‘… salvation ultimately means creation healed.

In Isaiah 19:22, God promises to hear humanity’s cries and heal them. In Isaiah 57:19, he pronounces, ‘Peace, peace, to the far and near…’, and pledges, ‘And I will heal them’. Jeremiah 3:22 says, ‘Return, O faithless children, I will heal your faithlessness’. When God’s people truly turn to him, he promises to ‘… heal their land’ (2 Chronicles 7:14).

The Old Testament word for peace— shalom—means: comprehensive wellbeing and healthy people in a flourishing land. Jesus applied Isaiah 6:9–10 to himself, proclaiming that if people would turn to him, he ‘… would heal them’ (Matt 13:15). Jesus was the Great Healer. His healing miracles powerfully signalled the presence of God’s kingdom. Ultimately, the Bible promises a healed and restored ‘… new heavens and a new earth’ (Isaiah 65:17; 66:22; 2 Pet 3:13).

Of course, the gospel is about justification by faith, forgiveness and new birth for each of us. But the larger truth that encompasses the healing of individuals is that families, societies, nations and all of creation are restored to true shalom.

The prophet Isaiah says of the Messiah: ‘Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases ... he was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed’ (Isa 53:4–5). Peter echoes this when he writes: ‘He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from sins, we might live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed’ (1 Pet 2:24).

I hope you all have a blessed Easter as you ponder what Jesus Christ has done for us.

by David Wardle(c) 'War Cry' magazine, 10 March 2018, pp20-21. You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.