You are here

Who is This Man? Ko wai tenei tangata?

Jesus has been depicted in every culture and corner of the earth. But who is he? Do we dare to see him as a Māori warrior, a black man or even a New York taxi driver? Jesus is—put simply—everything.

Jesus is the most depicted person that ever lived. We all recognise his image—the long hair, beard, tall slender frame, and calming demeanour. So when Richard Neave, a medical artist and expert in forensic anthropology, created a realistic depiction of what Jesus may have looked like (see picture centre right), the results were shocking: he seemed to resemble a New York taxi driver.

Jesus’ facial features were gleaned from first-century Jewish skulls and other archaeological data. Neave reasoned that Jesus would have been around 1.7 m (5’ 5”). His lifestyle would have made him muscular but slight, and probably as rough as old leather.

In her new book What Did Jesus Look Like?, historian Joan Taylor says Jesus would have had Arabic-like features. ‘Judaeans of this time were closest biologically to Iraqi Jews of the contemporary world,’ she says. According to cultural data, his black, curly hair would have been short, and his beard closely cropped using a knife. ‘I think what you would recognise Jesus as being was just really someone who looked very poor,’ says Taylor.

All depictions of Jesus are imaginative, of course. Biblical accounts are stubbornly silent on what Jesus actually looked like. The way we have depicted Jesus over the ages says a lot more about us than it says about him. It is telling that Neave’s original depiction of Jesus was later modified to give him a more dignified expression, and dare-we-say-it, more attractive appearance. We do like our heroes handsome and powerful!

The fact that the Bible gives us no clue about what Jesus looked like, is God’s first clue to us: he does not judge by human standards. In Jesus, he was about to turn all our expectations of power, success and even divinity inside-out.

Knowing the unknowable

Film depictions of Jesus often show him calm and emotionless, moving above the fray—the ‘Prozac Jesus’, as author Philip Yancey calls him.

But this is not the Jesus we find in the Bible. It’s perhaps surprising to discover how much Jesus was a people person—he constantly allowed himself to get distracted by passersby (no doubt an annoyance to the disciple keeping his schedule). Jesus seemed to build rapport almost instantly. He was easily moved by others. As Yancey points out, Jesus was generous with his compliments—‘your faith has healed you!’ he declared, deflecting credit away from himself. But he also got angry and impatient. ‘Are you still so dull?’ an exasperated Jesus snaps at the disciples (which, quite frankly, doesn’t seem very ‘Christian’).

He cried openly and accepted public displays of affection. He was an incredibly vulnerable man—would you ever face up to your friend and ask, ‘Do you love me?’ Well, Jesus did!

He was not play-acting at being human. Jesus felt things fully, he lived life deeply. In many of our depictions of Jesus, we seem to resist his humanness. It’s as if we would rather he kept a dignified distance. But Jesus mucked in with our humanity.

In Jesus, the impenetrable distance between heaven and earth collapsed into nothing. Through Jesus, God is saying: ‘Here I am. I am with you.’ Because of Jesus, we can know the unknowable. We have seen the invisible God.

The architect

It’s important we understand Jesus as a fully-fledged Jewish man, because there is no doubt that his followers believed he would be the Jewish King—the Messiah who had been prophesied. He would return Israel to freedom and prosperity. It was only a matter of time before an army would rise up to overturn the Roman Empire.

Then, just as Jesus was reaching the height of his fame and popularity, he presented his manifesto. This time he spoke plainly, not in parables. And quite frankly, it was confusing. Weird. Offensive even.

‘Blessed are you when you are “poor in spirit”,’ says Jesus (see Matthew 5–7 for the full account). When you grieve, when you’re humble, merciful, pure-hearted and love peace.

The people were expecting a declaration of war. Instead, they got a manifesto for meekness. ‘They were looking for a builder to construct the sort of home they thought they wanted, but [Jesus] was the architect, coming with a new plan that would give them everything they needed, but within quite a new framework,’ says Tom Wright, in Simply Jesus.

Many complex influences collided to culminate in Jesus’ death. The Romans were determined to stamp out any threat to their rule. But Jesus also failed to meet the Jewish expectations of the Messiah—so they concluded he must be an imposter. He was crucified as a traitor to Rome and blasphemer before God.

But the Bible claims the impossible—that Jesus very thoroughly, and very bodily, came back to life again. Wright makes the point that this story was as strange then as it is today—it had never happened before; it has never happened since. ‘The stories don’t fit … They seem to be about a person who is equally at home “on earth” and “in heaven”. And that is, in fact, exactly what they are.’

Jesus was revealed as the longed-for King; the Messiah. But not in any way we would recognise. He would not rule in time and space. Instead, he continues to rule through an unseen kingdom. He did not overcome with power, he infiltrated us with love. He did not stake out his greatness, he subverted us with grace. These truths continue to up-end us today.

How different are we to those first-century followers who wanted a king of power? We try to fit Jesus into our self-built values of consumerism, wealth, power and success. And Jesus is still refusing to enter that building. He is still insisting on being the architect of a whole new way.

For all people

There is a joke that the greatest miracle Jesus ever performed was being a white man in First Century Israel. As the dominant culture became European, images of Jesus became blue-eyed and pale-skinned. And so Jesus became yet another symbol of colonial oppression.

Yet every culture in the world has appropriated Jesus for themselves. Artists have portrayed Jesus as black, as Asian, with dreadlocks, and with Celtic red hair.

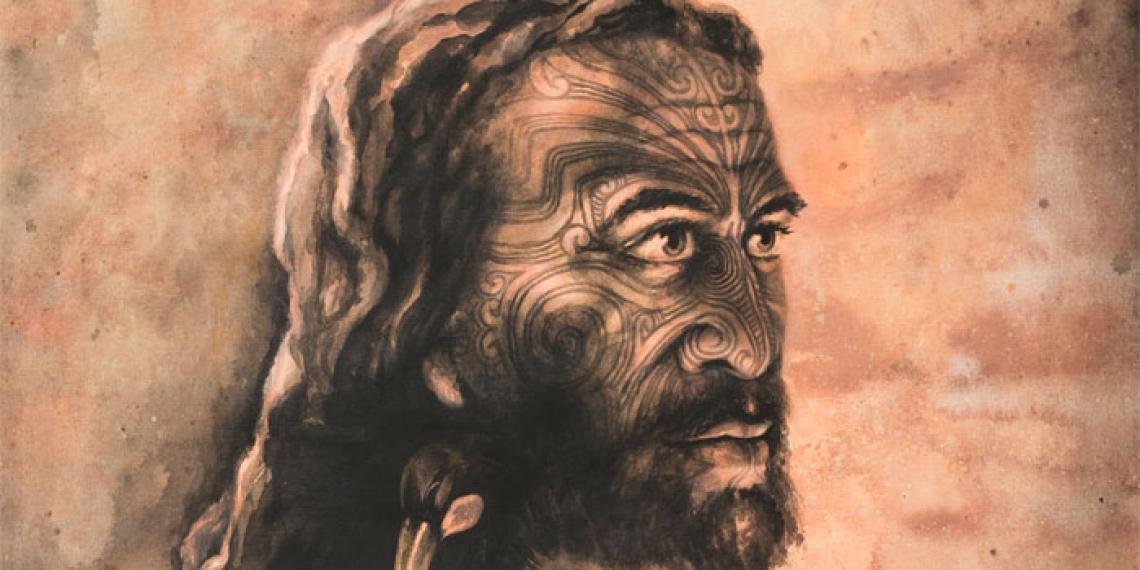

In Aotearoa, Sofia Minson has beautifully re-imagined Jesus as Māori. He is a warrior, a chief—but instead of proving his greatness with war and utu, Ihu Karaiti has shown us a new path. He proves he is the great Atua by coming in forgiveness and peace.The miracle of Jesus’ life is that he lives on as part of every culture and every historical nuance. The ability of Jesus to transcend culture, and yet fit within every culture, shows us that God really is with us.

The idea that Jesus can ‘be my best friend’ is often mocked. But, actually, isn’t that the miracle of Easter? The divide between us and God was shattered. We can know God, and even call him friend. God and humanity were never meant to be separate. In Jesus, we were brought back into intimate relationship with each other.

Jesus is everything

But that was just the beginning. The reverberations of Jesus’ life and death and life again, can be felt through the cosmos. ‘ “Heaven” and “earth” are not like oil and water, resisting each other and separating themselves out,’ says Wright. He argues that the Bible sees heaven and earth not as separate, but as interlocking and connecting.

During his lifetime, Jesus’ constant refrain was, ‘The kingdom of heaven is near!’ ‘Can’t you feel it?’ he seemed to whisper. When Jesus taught us to pray, he said, ‘Your will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.’ He showed us heaven—through his miracles, his healing, his compassion and grace. ‘A new power is let loose on the world, the power to remake what was broken, to heal what was diseased, to restore what was lost,’ sums up Wright.

The defining moment in history, when Jesus rose from the dead, was the beginning of a whole new creation that is still revealing itself today. Within three decades of Jesus’ death and resurrection, Paul—who had been an orthodox Jew until he discovered Jesus—described how ‘God placed all things under [Jesus] feet and appointed him to be head over everything … who fills everything in every way’ (Ephesians 1:23).

This vision of Jesus is not just as a personal saviour, although that is important. It goes further. He brings salvation to the universe—he is restoring the whole world to its original and perfect creation. Whenever we act according to the Kingdom of Jesus—when we bring healing, love, grace and peace—we become active participants in this new creation.

Who is Jesus? He is everything.

by Ingrid Barratt(c) 'War Cry' magazine, 24 March 2018, pp6-9. You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.