You are here

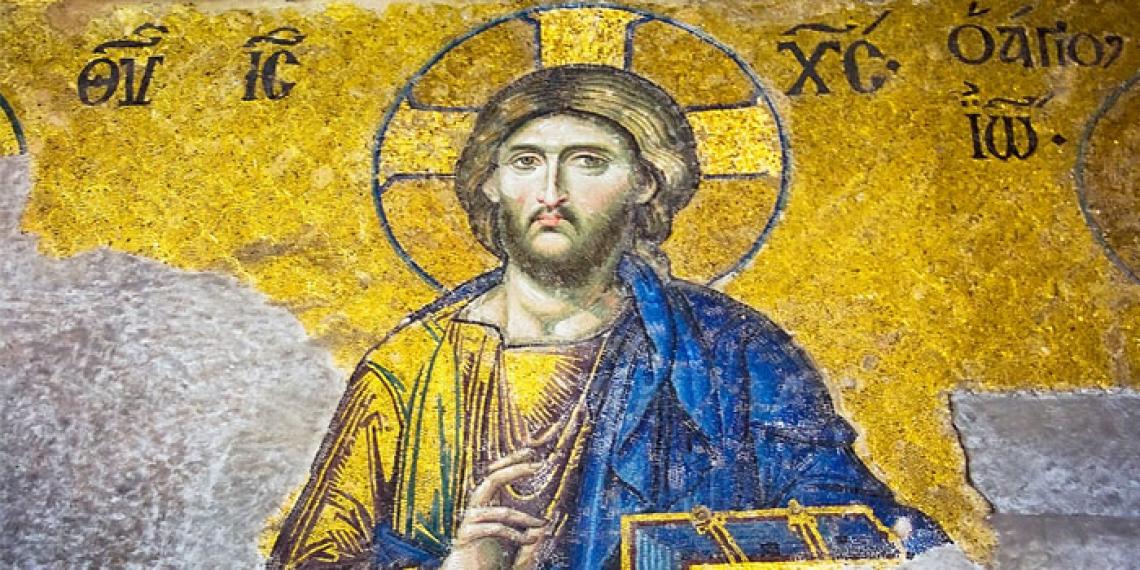

The prophet still speaks today

What do you think is the most boring bit of the Bible? Go on, admit it; there are parts of the Bible you don’t enjoy. There are parts you would rather avoid. Parts that are weird, gruesome, X-rated even. There are parts that just don’t seem to make sense.

Most of us like the stories the Bible contains. We can picture Jesus calming waves or Moses floating in a basket. Most of us can find helpful words amongst the letters and comforting words in the Psalms. But what do you do with the Minor Prophets?

You know—those 12 weird little guys at the end of the Old Testament with unpronounceable names and that you can never find when you are flicking through the Bible in a hurry. Many Christians just don’t even go there. Those books are just too bizarre. After all, at first glance they seem to just say the same thing over and over: doom, gloom, destruction, judgement.

We get the message: God is not a happy camper!

So why should we read these Minor Prophets? Well, we should read them because Salvationists believe ‘that the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments were given by inspiration of God, and that they only constitute the Divine rule of Christian faith and practice’. This means that even ‘the boring bits’ in the Bible are inspired by God. It means that even the Minor Prophets have something to say to believers today.

So then, the real question is: how do we find out what that message is all about?

Context is the key. We must look at their historical context. That is, we must look at why the Minor Prophets were written, when each was written, and what was going on at the time for the people they were originally written to. We’re going to do just that with the book of Micah.

Micah is a book that many Christians will know one verse from: And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8). On the basis of this verse, many have presumed that Micah is a book about social justice. But is it? Well, it will take a little digging to find out.

Old Testament Prophecy

First though, since we are going to be looking at a prophetic book, we need to think about what a prophet was in the Old Testament and how prophecy worked back then.

In the Old Testament, prophecy wasn’t just about predicting the future. A prophet was someone who spoke God’s words on a matter. Prophets were God’s mouthpieces. God put his very words in their mouth, which is why their oracles would often begin with, ‘the word of the Lord came to … the prophet’.

Those words from God might be a prediction of something that would happen in the future (foretelling), but more often they would be a message concerning the present situation (forth telling). Both of these aspects are clearly seen in the book of Micah. In it, we find predictions about Christ and the Messianic Age, but also a very important message that addressed the people’s disobedience against God and the problems this was creating for them.

The role of the prophet changed throughout the Old Testament. Jews recognise Moses as the first and greatest prophet. Like so many prophets after him, Moses had an unexpected encounter with God where he was called to a special task and, despite feeling reluctant, delivered his unpopular message.

In the early days of the monarchy in Israel (10th and 9th century BCE), the role of the prophet was to be God’s voice to keep the king on track. We see this with Nathan (2 Samuel 12) and Elijah (1 Kings 21). At that time, the prophet’s messages were oral, but this changed in the 8th century BCE.

From around the 8th century, the prophet’s messages were written down. These writings form the prophetic books that we find in the Old Testament today. These, the ‘literary prophets’, no longer addressed just the king; their message was for the whole nation of Israel. After all, at this time the whole nation was in trouble and needed to hear from God.

The Assyrian Empire was expanding and threatening the 10 northern tribes of Israel. In 722/721 BCE, the Assyrians succeeded in conquering the northern tribes and relocating many of its people. God spoke to his people at this time through the prophets, encouraging them to give up their sins (particularly the sin of idolatry) and to turn back to God. The prophets saw the Assyrian invasion as God’s justified punishment for Israel’s disobedience, so through many of the prophets we hear a tone of judgement.

Around 150 years later, the Assyrian Empire was toppled by the powerful Babylonian Empire. The Babylonians were now threatening the two remaining southern tribes. God spoke again to his people. The prophets’ messages were stern and urgent. They pleaded for repentance and a return to God. They declared that the people had brought this disaster upon themselves.

In 586 BCE, the Babylonian armies did capture the south, and many of its people were taken into exile in Babylon. Here, we see a significant change in the tone of prophecy. The prophets—after the exile—not only encouraged God’s people in their work at that time, but they also held out a messianic hope. They looked forward to a better future that was bigger than just the physical restoration of Israel. They looked forward to a future that was wider than just Israel.

Being able to place the prophets into his or her (yes, there were a few women prophets) place in Israel’s history makes a huge difference to how we read them.

Micah’s historical context

So, back to Micah. Where does he fit into Israel’s history?

The opening verses of Micah (as with a number of the prophetic books) conveniently answer this question. They tell us that Micah prophesied during the reigns of Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah, which means his book was probably composed between around 750 and 680 BCE. They also tell us that Micah was from the south, a small rural town called Moresheth. All of this tells us that Micah would have witnessed from a distance the fall of the 10 northern tribes to the Assyrian army.

I wonder what that was like.

I wonder what Micah saw and heard.

I wonder how that impacted his life every day.

I wonder what fears Micah held for his friends and family as they lived with the Assyrian army just up the road.

Micah’s literary context

We must consider these things as we read Micah. His historical context matters, but we must also consider his literary context. The form that the Bible comes to us is as a piece of literature. No ordinary piece of literature, of course, but literature nonetheless. And so we must remember as we read it.

Micah is poetry. Not lilty, rhymy poetry; that was not how the Jews did poetry. But its words were carefully chosen and arranged for their sound as well as their meaning.

Poetry appeals to the emotions. It can say more than prose can, but in a lot fewer words. This is because poetry paints pictures. It uses clever word plays, puns, metaphors and alliteration to help get its point across. All these literary features can be seen in Micah.

Jewish poetry also uses parallel lines. This is where one line makes a statement and the following line reinforces it by saying the same thing, but in a different way to emphasis the point.

In Micah we find repetition. Three times God’s people are told to hear or listen (from the same Hebrew word shama). This instruction is significant as each time it is given (Micah 1:2, 3:1 and 6:1), it marks the beginning of a new section of the book. Each of the three sections consists of a longer section of bad news and concludes with a shorter section of good news.

So, this is how we shall divide Micah for our study. We will spend one week on the first and last sections, and two weeks on the longer middle section.

Now that we know a little about the historical situation of the book and the literary features to look out for, may God attune our ears to hear his voice—for God still speaks today! God has a message for his people, if we are willing to hear it.

By Carla Lindsey

Digging deeper

Ponder this: God communicates. Just stop there for a minute. We have a God who speaks. That is mind blowing! God is not a distant remote God, but one that seeks contact. He has things to say to us. Saint Teresa of Avila says, ‘It’s not that God doesn’t speak, it’s that his children are deaf.’ So, are you listening? Are you expecting God to speak to you?

God communicates through people. Okay, God doesn’t always speak through people. God can speak any way he likes, but God often uses people to be his messengers. We see this in the Old Testament and we see it today. The prophets in the Bible were ordinary people, from all walks of life. They weren’t perfect people, but what set them apart was their commitment to God. They were totally devoted, so much so that even though many of them were afraid and felt inadequate, they found the courage to go against the grain and deliver God’s message. Might God be trying to speak to you through someone you wouldn’t expect?

The way God communicates can change. It’s not like God has only one communication method, and that’s it for all time. The way prophecy worked through the Old Testament changed, and it changed again in the New Testament. God’s communication style isn’t static, but dynamic. It changes to fit the context. That’s because God’s desire is to be understood, and so he communicates in ways that will have meaning to people in their particular context. Might you be limiting the ways that God can speak to you?