You are here

The prophet still speaks today- Part 4

Christianity is full of tension. What I mean by that is that Christian theology is full of ideas that are contradictory, yet true. For example, Christians believe firmly in one God, yet they also believe God is three persons. They believe Jesus is fully human, but also fully divine. They believe that Jesus truly died, yet is alive; that creation is good, but also fallen; that salvation is a free gift, but something we need to accept and participate in. I could go on, but you get the idea. Seemingly opposing ideas like these are held in tension.

Micah chapters four and five are a prime example of this kind of tension. In these chapters we feel the tension as Micah swings between the bad news and the good news that are both part of his message. We also feel the tension as his message alternates between what was for the ‘right now’, and what was for the ‘not yet’. This is even more complicated for modern-day readers of Micah because we have to figure out what was for back then, as well as the ‘right now’ and the ‘not yet’!

These chapters are complicated! So, to make it easier to navigate them we will divide them into three sections and work through them one at a time.

Hope in hard times

Section one, Micah 4:1–8, opens with, ‘In the last days’. Now people can get hung up on the chronology of end-time events, but I think that to do that here is to miss the point. Micah isn’t talking about when and how those events will come about. His point was to give hope to people who were experiencing difficult times by reminding them that God had good things for them in his big plan. Micah was pointing to a future time to encourage people to face the reality of their current struggles in the light of God’s good plans for his people.

Here is what Micah says ‘the last days’ (or as he calls it later ‘that day’) will look like:

In the last days

the mountain of the Lord’s temple will be established

as the highest of the mountains;

it will be exalted above the hills,

and peoples will stream to it.

Many nations will come and say,

‘Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord,

to the temple of the God of Jacob.

He will teach us his ways,

so that we may walk in his paths.’

The law will go out from Zion,

the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

He will judge between many peoples

and will settle disputes for strong nations far and wide.

They will beat their swords into ploughshares

and their spears into pruning hooks.

Nation will not take up sword against nation,

nor will they train for war anymore.

Everyone will sit under their own vine

and under their own fig tree,

and no one will make them afraid,

for the Lord Almighty has spoken.

All the nations may walk

in the name of their gods,

but we will walk in the name of the Lord

our God for ever and ever.

‘In that day,’ declares the Lord,

‘I will gather the lame;

I will assemble the exiles

and those I have brought to grief.

I will make the lame my remnant,

those driven away a strong nation.

The Lord will rule over them in Mount Zion

from that day and forever.

As for you, watchtower of the flock,

stronghold of Daughter Zion,

the former dominion will be restored to you;

kingship will come to Daughter Jerusalem.’ (Micah 4:1–8)

If you have been following this series, you will notice that these verses stand in direct contrast to chapter three. In Micah 3, God had condemned the corrupt leaders of Jerusalem. Here, Micah looks ahead to what things will be like under God’s leadership. It’s quite a contrast!

In chapter three, God was absent; here God himself is present. In chapter three, Jerusalem and her temple were destroyed. Here, they have been restored and God is seen ruling from Jerusalem, which is described as the highest mountain to show its supremacy. In chapter three, there is bloodshed; but here it is replaced with universal peace. In fact, weapons will no longer be needed for war. They will be recycled for more productive purposes.

In chapter three, the judges were wicked and corrupt. Here, God judges with fairness, settling disputes. In chapter three, the poor were taken advantage of. By contrast, in these verses, the lame —who represent the weak, the sick, and the outcast—are taken in and included. God is portrayed as the good shepherd gathering in his sheep.

In chapter three, the priests and prophets don’t deliver God’s words. But here, God himself teaches the people directly. These verses describe people from all different races and places streaming to Jerusalem to be taught by God and then returning home taking his teaching with them. Such a beautiful picture! How wonderful God’s reign will be! This is good news!

But it’s not here yet. Obviously. The world Micah’s original audience lived in and the world in which we live is miles away from the one described in Micah 4:1–8. This was the tension this passage’s original audience lived with: the hope of a glorious future with God as their king, but the reality of a very difficult present. Micah 4:5 records the people’s response to the other verses in this section that describe God’s rule:

All the nations may walk

in the name of their gods,

but we will walk in the name of the Lord

our God for ever and ever.

This is how God’s people dealt with the tension. They asserted that in the light of the future, their best response was to commit themselves to God now. Other people were free to worship how they chose, but the Israelites would walk in the name of God.

Good and bad news

The second section is Micah 4:9–5:4. Several clues in this passage have led scholars to conclude that its historical setting is the siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC, during the reign of Hezekiah. If that is the case, then as Micah wrote, the Assyrian army, which had already destroyed many small towns, was now trying to break down the walls of Jerusalem.

This section alternates between the bad news about the present, and the good news about the future. The bad news was that nations had gathered against Israel and they would eventually leave the land and go into exile. The good news was that it was ultimately God, not the other nations, who was in control, and in the end God would redeem his people.

The climax of this section comes in the good news announcement that redemption would come through a messianic ruler:

But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah,

though you are small among the clans of Judah,

out of you will come for me

one who will be ruler over Israel,

whose origins are from of old,

from ancient times …

He will stand and shepherd his flock

in the strength of the Lord,

in the majesty of the name of the Lord his God.

And they will live securely, for then his greatness

will reach to the ends of the earth.

And he will be our peace

when the Assyrians invade our land

and march through our fortresses … (Micah 5:2,4–5)

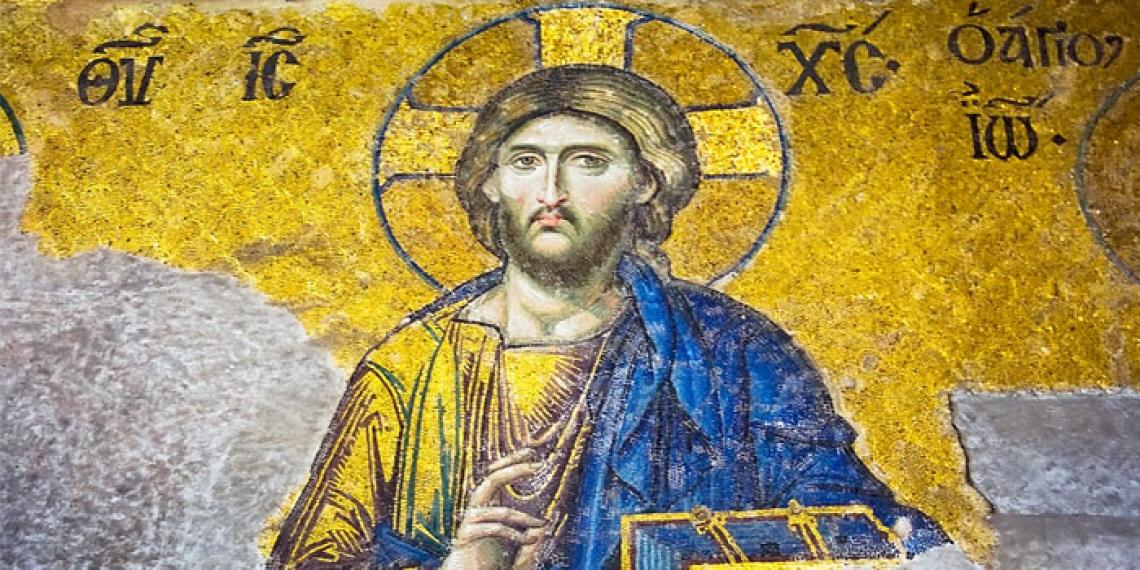

This ruler would come from a small and insignificant place, Bethlehem the town of King David, yet he would be great. He is described as a good shepherd. These verses link him to the ancient past as well as a glorious future. And just as in Micah 4:1–8, this ruler would bring universal peace. New Testament writers recognised that this prophecy was fulfilled in Jesus Christ.

True hope is in God

In the final section, 5:5–15, Micah describes what the ruler’s peace will look like. Micah 5:5–6 tells us that peace will look like the elimination of the enemies of God and his people. Micah 5:7–9 tells us that peace will look like Israel finding her strength again. And Micah 5:10–15 tells us that peace will look like a people who are pure. Thus Micah describes the removal of all the things that offend God:

‘In that day,’ declares the Lord,

‘I will destroy your horses from among you

and demolish your chariots.

I will destroy the cities of your land

and tear down all your strongholds.

I will destroy your witchcraft

and you will no longer cast spells.

I will destroy your idols

and your sacred stones from among you;

you will no longer bow down

to the work of your hands.

I will uproot from among you your Asherah poles

when I demolish your cities.’ (Micah 5:10–14)

We get it: ‘God will destroy!’ The phrase is repeated to emphasise the point. Those things that offend God must go. These aren’t very nice words, but they were necessary. Military strength, walled cities, idols and witchcraft would give no real security, no true lasting peace. They provided only false hope. True hope was found from depending on God alone.

True hope is still found from depending on God alone. These days, we may not trust in chariots or graven images, but there are plenty of other things we put our hope in. Our jobs, bank accounts, family/friends, technology, the good things we do—even in church. Micah chapters four and five remind us that trusting in any of these things gives false hope. Hope based on human achievements will fail. Only hope built on God will last.

Chapters four and five also remind us that we aren’t promised an easy life. God does not promise to rescue us from all our problems. Life is a mixture of good news and bad news. But we, like the ancient Israelites, have a future hope to look forward to. The question is: how will we live today in the light of that hope?

Ponder This

Micah chapters four and five paint a picture of God’s rule. God’s rule is described as one of peace and justice, where everyone is content, included, and lives without fear. So, if this is God’s intention for the world, how can we build communities like that now?

How do you balance the tension of the ‘not yet’ and the ‘right now’? When the pressure is on in your present circumstances, how can you remind yourself of God’s future?