You are here

Off to Jerusalem

‘Off to Jerusalem’

In 1888 The Salvation Army’s colony commander of New Zealand, Colonel Josiah Taylor decided to officially commence ministry within Māori communities.

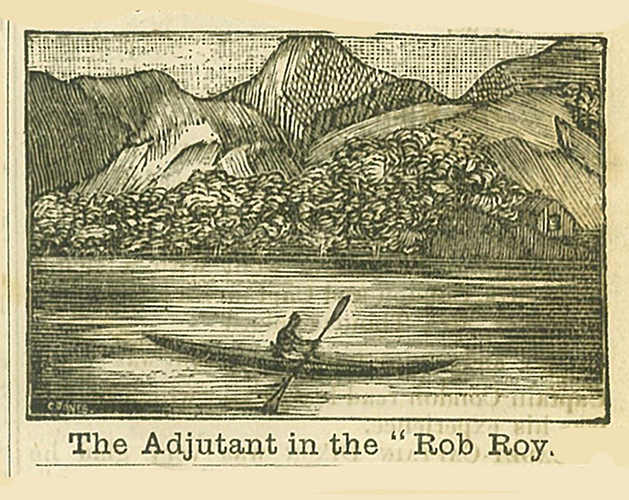

‘Off to Jerusalem’ was the title of a series of articles that featured in the November 1889 weekly editions of The Salvation Army’s publication The War Cry. The articles were accompanied by several line illustrated images and described the personal experiences and observations of those who visited and lived amongst Māori communities along the banks of the Whanganui River.

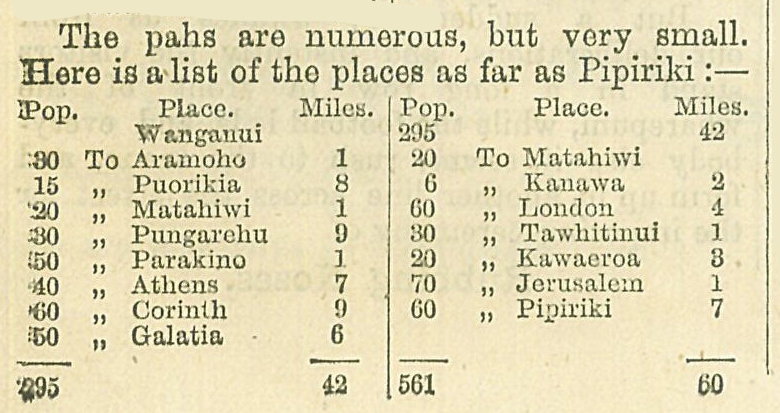

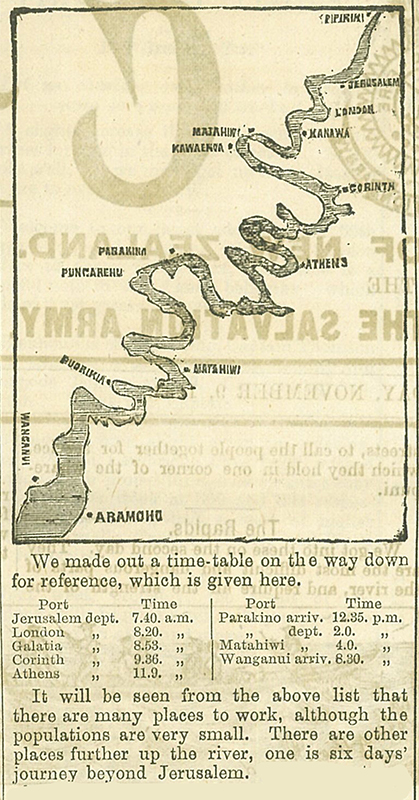

Travel was by waka, ‘these canoes are long and narrow made from the trunks of large trees… ours was sixty feet long… we had no feeling of danger although we had heard a great deal about the rapids and rather longed to see them… The morning was delightful - clear blue sky … hills rising above each other in the distance, towering towards heaven covered with foliage… together with the Salvationists in view made it an indescribable sight.’ (2 November edition)

Travel was by waka, ‘these canoes are long and narrow made from the trunks of large trees… ours was sixty feet long… we had no feeling of danger although we had heard a great deal about the rapids and rather longed to see them… The morning was delightful - clear blue sky … hills rising above each other in the distance, towering towards heaven covered with foliage… together with the Salvationists in view made it an indescribable sight.’ (2 November edition)

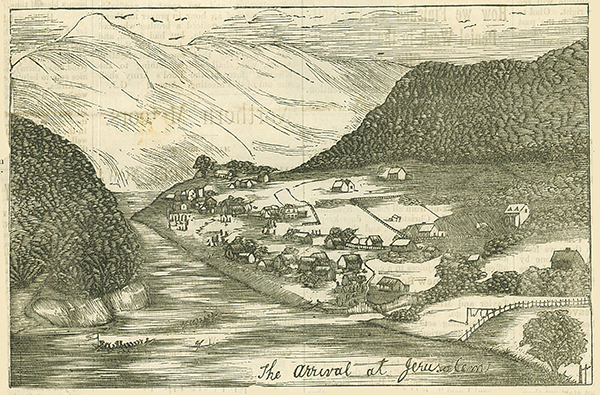

Names for these infamous rapids included, Kaiwaka, ‘eat the waka’ and Whakamatuku, ‘frightened’, which were unsettling for the traveller. ‘On the afternoon of the third day, we reached Jerusalem. The people were waiting for us on the bank... Further up the pah [sic] stood Tamatea, sword in hand and dressed in Maori [sic] costume with several Salvationists … enthusiastically shouting, singing and waving their arms and bodies to the tune. ’ (9 November edition)

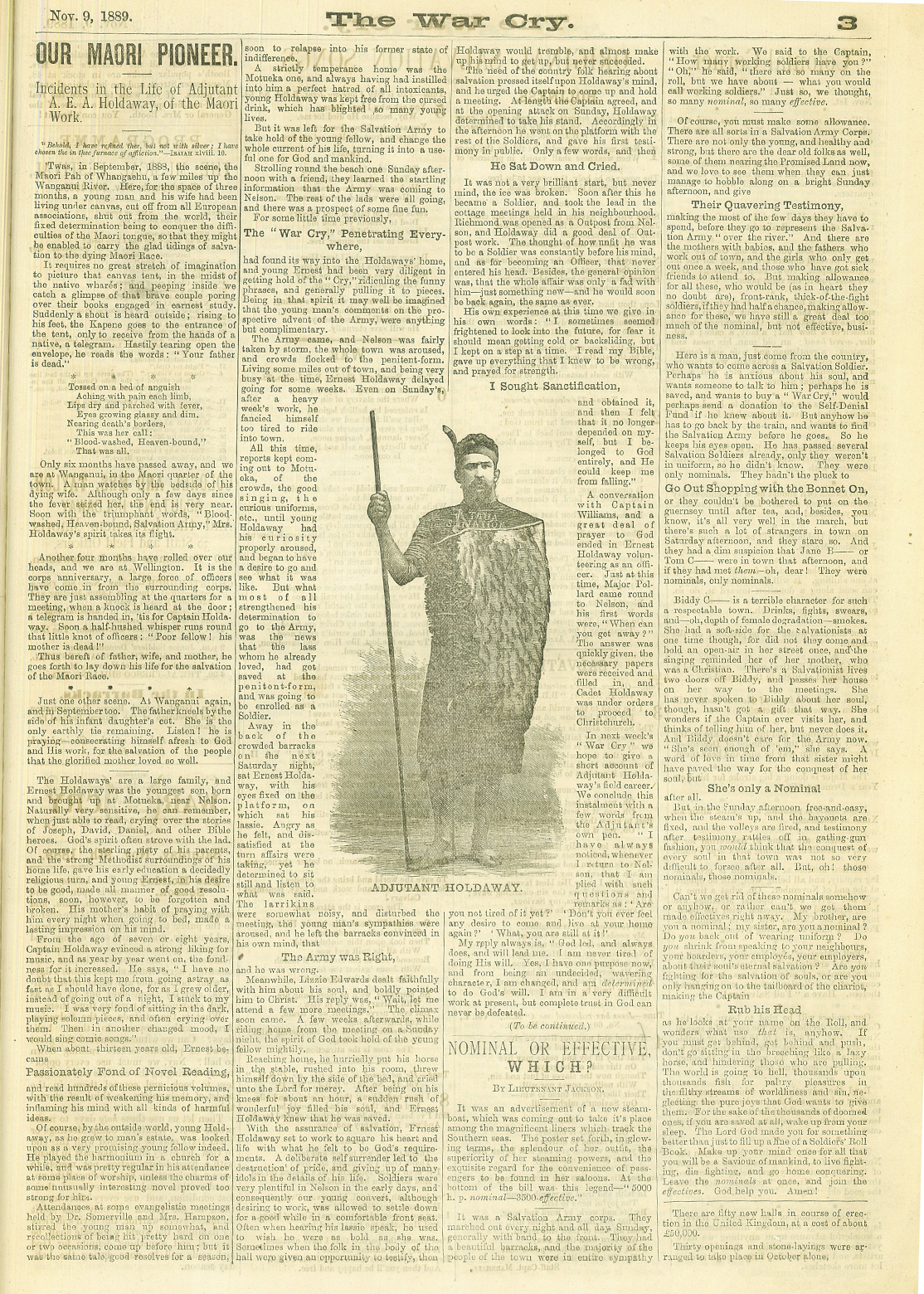

Ernest Holdaway – ‘Our Maori [sic] Pioneer’

Captain Ernest Holdaway and wife Lizzie (Edwards) were married in 1888, arriving on the river in the same year. Holdaway contributed an autobiographical article in The War Cry of 9 November 1889, titled, ‘Incidents in the Life of A.E.A. Holdaway, of the Maori [sic] Work’ at ‘the Maori [sic] Pah [sic] of Whangaehu, a few miles up the Wanganui [sic] River. Here for the space of three months, a young man and his wife had been living under canvas, cut off from all European associations, shut out from the world, their fixed determination being to conquer the difficulties of the Maori [sic] tongue, so that they might be enabled to carry the glad tidings of salvation to the dying Maori [sic] race.’

While there, he received news of his father’s death and three months later, ‘A man watches by the bedside of his dying wife. Although only a few days since the fever seized her, the end is very near.’ Left to care for his infant daughter, he soon mourned the death of his mother. However Holdaway writes, ‘Thus bereft of father, wife and mother, he goes forth to lay down his life for the Maori [sic] Race.’

While there, he received news of his father’s death and three months later, ‘A man watches by the bedside of his dying wife. Although only a few days since the fever seized her, the end is very near.’ Left to care for his infant daughter, he soon mourned the death of his mother. However Holdaway writes, ‘Thus bereft of father, wife and mother, he goes forth to lay down his life for the Maori [sic] Race.’

Holdaway was born in Motueka of Methodist parents, describing himself as a ‘sensitive child’, enjoying music and reading and ‘his mother’s habit of praying with him every night when going to bed made a lasting impression on his mind.’

The Salvation Army arrived in Nelson in February 1884 and on reading his first War Cry, Holdaway remembers how he ridiculed the ‘funny phrases’. However, his curiosity was further increased once he learnt that ‘the lass (Lizzie Edwards) whom he already loved had got saved at the penitent form and was going to be enrolled as a soldier.’ Once enrolled, Holdaway involved himself in the Army’s work in neighbouring Richmond, an outpost of the Nelson Corps. His desire to be an officer was confirmed when Major Pollard (co-founder of the Salvation Army in New Zealand in 1883), visited the area. Holdaway commenced officer training in Christchurch in 1885 and appointments in North Canterbury and the East Coast preceded life on the river.

Holdaway’s guernsey, shown in the image, carries the words, ‘Te Taua’, for ‘Te Taua Whakaora’, translating as ‘the Army that causes life’. Later ‘taua’ was substituted to ‘ope’, ‘Te Ope Whakaora’, ‘the Army that brings life.’