You are here

Set free

Over 100 years ago The Salvation Army made history, creating New Zealand’s first rehabilitation programme for alcoholics. This heritage continues today, with The Salvation Army still at the forefront of addiction services in New Zealand. But it all began with the dream of an island sanctuary—an ‘inebriates retreat’. In this excerpt from Set Free, a history of the Army’s care for alcoholics and addicts by Don and Joan Hutson, we look back at how the Army first brought hope to the hopeless.

Few had seen him sober and most crossed the road when he hove into sight. Unshaven and unwashed, he lurched from one pub to another. He had his favourite park bench but even there the demon that plagued him raged inside. Hidden (he thought) under his coat was half a bottle of flavoured methylated spirits. He needed no introduction. Everyone knew the town drunk.

Less noticeable, but just as surely on the slippery slope, were others from all walks of life. They and their families condemned to a crazy Jekyll and Hyde existence. Physical abuse was common, and society’s response to the habitual drunkard was a mixture of disgust and fear, leading eventually to either prison or a lunatic asylum. The idea of rehabilitating the drunkard was inconceivable.

History in the Making

The Salvation Army brought to New Zealand a powerful message that the most enslaved drunkard could be set free—redeemed and transformed. They had seen it for themselves. This brought hope to the South Seas colony of Aotearoa.

It began with a dream, it was said, in the fertile mind of The Salvation Army’s founder. General William Booth had visualised a retreat for habitual drunkards, an inebriates’ island, no less. A place of healing—now, that would be ideal. Impractical, but ideal.

But in 1906 came a heaven-sent opportunity. The New Zealand Government passed the Habitual Drunkards Act, and approached The Salvation Army to help set up the first treatment facility for alcoholics in New Zealand.

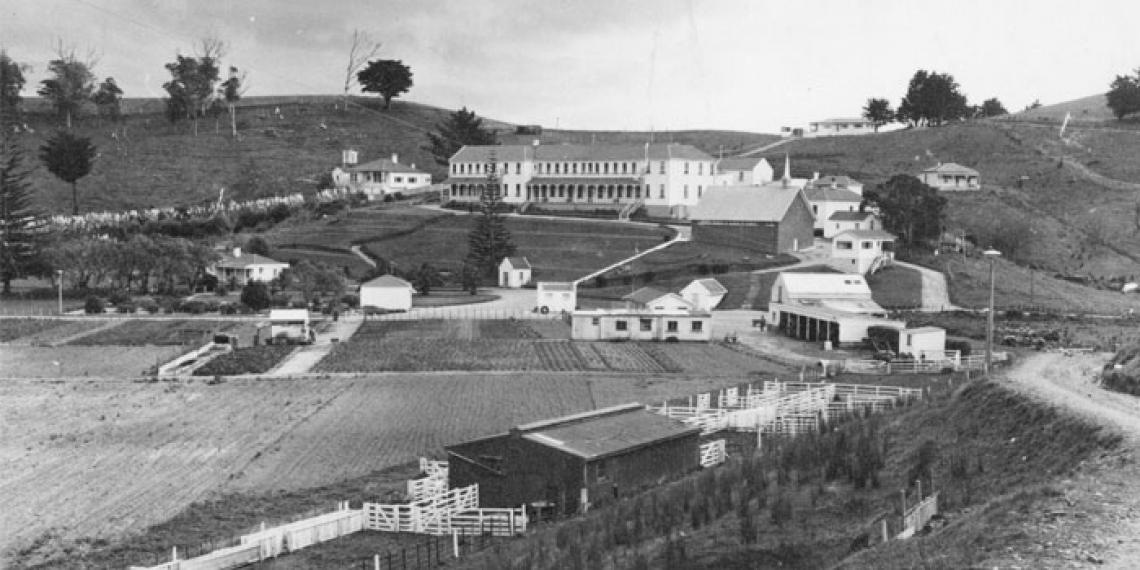

In September 1907, The Salvation Army officially opened an ‘inebriates’ retreat’—an island just off Auckland for the purpose of rehabilitation. Then, in 1908, swept away with enthusiasm, the Army purchased a neighbouring 200-acre island with beautiful beaches and a warm climate, which they named Rotoroa Island. For the first time, alcoholics became patients, rather than criminals.

‘Hopefulness is the first element which our officers seek to implant in the hearts of their patients. And once the tendency to despair is removed … there begins to dawn a new hope, the work of reclamation … is well underway,’ reported The War Cry.

Just the Right Man

By the middle of the century, Pakatoa Island had become a retreat for women, and Rotoroa Island a facility for men. But the dream had begun to fade, with dwindling numbers of patients and rundown facilities. But in 1955, renovations were commissioned, and with it, a new era for the island and the treatment of alcoholism.

The Salvation Army’s two top leaders, Commissioner Hoggard and Colonel Cook, looked for ‘a man’s man’ to run Rotoroa Island, with an openness to new approaches to treatment—a manager with a heart for the alcoholic. Cook’s retentive mind led him to a recovered alcoholic seaman, now a Salvation Army officer in Nelson. He first encountered this man in India and had followed his progress with interest. This was Senior-Captain (later Major) Robert McCallum, now aged 56. Both leaders had no doubt that Bob McCallum was just the right man—God’s man—for Rotoroa Island.

Fighting Mac

Born in 1900, in Invercargill, McCallum was 14 when he ran away to sea on a sailing ship. By the end of World War I, Bob had joined the Royal Navy, which took him to such far-flung places as China, South America and the Mediterranean.

Bob’s world was a tough, hard-drinking world. A champion with his fists, ‘Red McCallum’—also known as ‘Fighting Mac’—boxed in the navy as a successful welterweight. On one occasion, he was sent off to represent the navy in the World’s Fair in South America. Boxing and booze made a potent and dangerous combination. After an unexpected defeat in a major boxing match, Bob, at 39, found himself in the grip of alcoholism.

Always broke, hardly ever sober and often in trouble, Bob began to fear for his life. Eventually, he found his way back to New Zealand and to the Richmond Mission in Christchurch, where two Christian missioners asked him a simple question: would he trust Jesus to be his saviour and guide for the future? Bob was no longer young and drink had taken its toll. But to be a Christian? He wrestled with God alone, made his decision carefully and was soundly converted. His days of drunkenness were over forever.

Seeking the drunkard

Bob’s first act was to declare his new faith and his newfound sobriety to his shipmates. His primary concern was to seek out men without hope. A missioner friend suggested he try The Salvation Army.

In the meantime, Bob and Claire Smith found each other, or as they put it, ‘the Lord brought us together’. Claire was a widow with a ready-made family, Bob had a longing for companionship, and both had a dedication and commitment to the Lord. Once married, the couple became soldiers of Devonport Corps.

Bob was 45 when God intervened again, calling the McCallums to become officers of The Salvation Army. Neither Bob nor his wife knew anything about running a Salvation Army church and, possibly because of their age, appear not to have gone through the Training College. They were given the rank of envoy and appointed to the little corps of Otahuhu, where they proceeded to work by trial and error. At first, they had no uniform, so until a tunic could be tailored, Bob led Salvation Army meetings in naval rig.

The McCallums worked hard. Claire was an articulate and vivacious speaker. ‘Envoy Mac’ was a man of few words, but his sympathy for the victims of alcohol was soon apparent. He visited the local jail at all hours and spent many hours in hotel bars. This was his world and he understood the language. In September 1966, The War Cry carried a description:

‘Early and late, he sought the drunkard and alcoholic, brought them to his quarters, talked to them, prayed over them and wrestled with their personal problems at home and at work. Often, one of these men would sit with Captain Mac in the front seat of his car and go with him everywhere for days on end. The congregation grew, and one Sunday there were 42 seekers at the Mercy Seat.’

Walking the Walk

Rotoroa Island needed firm but caring leadership. Rotoroa Island needed the McCallums. The couple packed their bags, and in 1956 made the lovely island their home. Upon arrival, Major and Mrs McCallum wasted no time. They were high-energy people, imaginative, good humoured and glad to be there. Word got around the island quickly: the McCallums talked the talk and walked the walk. They were also pragmatic. From his years in the Royal Navy, Bob McCallum was likely to run a tight ship.

Bob lost no time in training up his officer assistants. ‘Look,’ he would say to a new assistant, ‘Can you stand being cursed, sworn at, abused, thieved from, deceived and lied to and still love these men? If not, you are no good here.’

Bob did not depend on his having graduated from the University of Hard Knocks alone to give him the insight he needed for his job. He read widely, making a special study of law, medicine, psychology, psychiatry, police court procedure and prison chaplaincy. In addition, Bob determined in his heart that every possible aid would be used to reclaim these ‘patients’—the best of food, music, flowers, good books, games, bright surroundings, frequent personal interviews, concert parties from the mainland, visiting artists, and films—anything that might promote healing and reduce the connotations of penal servitude.

Regardless of what the captain had said to his assistant officers about their charges being difficult to love, Bob saw good in all these men. They might admit to being ‘toey’, especially in the first few weeks, but they were men with feelings of failure. By and large, they had been knocked around by life and now felt trapped. The whole atmosphere on the island lifted as the residents responded to the encouraging but direct approach shown by the McCallums. Bob’s family reported that he had a marvellous rapport with people, and it was not long before ‘Mrs Mac’ also knew every inmate by name. In her own inimitable way, Claire brought a special touch to island life.

A Tight Ship

Bob was a good manager and his naval training meant he was no walkover. He required everything to be shipshape and was a stickler for law and order. If ever there was an incident requiring a measure of discipline, the Major would interview the person concerned. At the end of the interview, he would say nothing. He would just go, leaving the individual wondering what was going to happen. He would think things through and was likely to wait until late afternoon of the day before boat day. Then he would simply say, ‘Tom, have your bags packed—be on the boat in the morning. Come back when you mean business.’ That would be it. No right of appeal. Just a straight direction.

Bob was also adamant that the boat timetable be strictly adhered to. If departure time was 6 am, that was when the boat would leave. If 1 pm was the time for the return trip, 1 pm it would be—a rule that apparently applied to everyone. An apocryphal story describes an afternoon when the boat left a dismayed Mrs Mac waving frantically from the wharf, all in vain!

While others criticised a system that saw inmates discharged ‘on to the wharf and into the nearest pub’, whenever possible the pragmatic McCallums arranged for accommodation for those serious about recovery—often calling on their own family now living in Auckland.

‘Dad used to get us to meet the boat often,’ recalls the McCallums’ daughter, Bev, ‘either to escort someone or take care of men leaving the island. When lodgings were found, we would nurture them as best we could, often attending to them when they rung at all hours of the day or night. I would go and find them in the city, bring them home and shelter them for a while.’ Opening their homes to recovering alcoholics was something the whole family thought of as normal.

Soul saving

Captain Mac’s primary goal was to see men with changed lives, and incidents of ‘soul saving’ became more common. ‘The Captain had a big heart for the residents,’ said one staff member. ‘He was a very spiritual man and spoke “straight” with the men about spiritual matters.’ Frequently, he would pause in his day’s work to help a man haltingly confess his need. It was no magic waving of a wand, and each man was different, but it had worked for Captain Mac. Surely, God would hear his prayer!

Some hated the ‘religiosity’ of a graceless few and left the island confirmed in their unbelief. Others were agnostic, but wished with all their heart that they could believe, showing every sign of having started on their journey. A significant few knelt at the place of prayer in the chapel (or in the cowshed) and were ‘born again’.

Excerpt from:

Set Free: One Hundred Years of Salvation Army Addiction Treatment in New Zealand 1907–2006 By Don and Joan Hutson

Order from Salvationist Resources— $20

p: (04) 382 0768 | e: mailorder@nzf.salvationarmy.org